Book or movie: Which JAWS has more bite?

You can catch The Shark Is Broken from 25th July 2023 at the Golden Theater, New York, NYC.

I was all of two-and-a-half years old when Jaws first frightened movie-goers out of the water in 1975. It wasn’t until Spielberg’s big fish story surfaced on the small screen in November of 1979 that I finally got in on the action, however; and after that, nothing was ever quite the same for me.

My mom loved horror and science fiction films and had already begun introducing them to me by that time, in particular the classic Universal monster movies: Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Wolf Man, along with various made-for-TV fare (TV movies were a big deal in those days). Jaws captivated me because it was simply on a different level than anything I had seen before. For most of the movie, the shark was an unseen menace, occasionally snatching people beneath the waves to the accompaniment of John Williams’ amazing score; and, unlike the monster movie creatures I was used to, sharks were real. Going out on the water could actually mean taking your life in your hands. If there was a shark around, it would know you were there long before you knew it was there; and if it decided to come after you, well, then, to quote a world-renowned shark expert, “Farewell and adieu…”

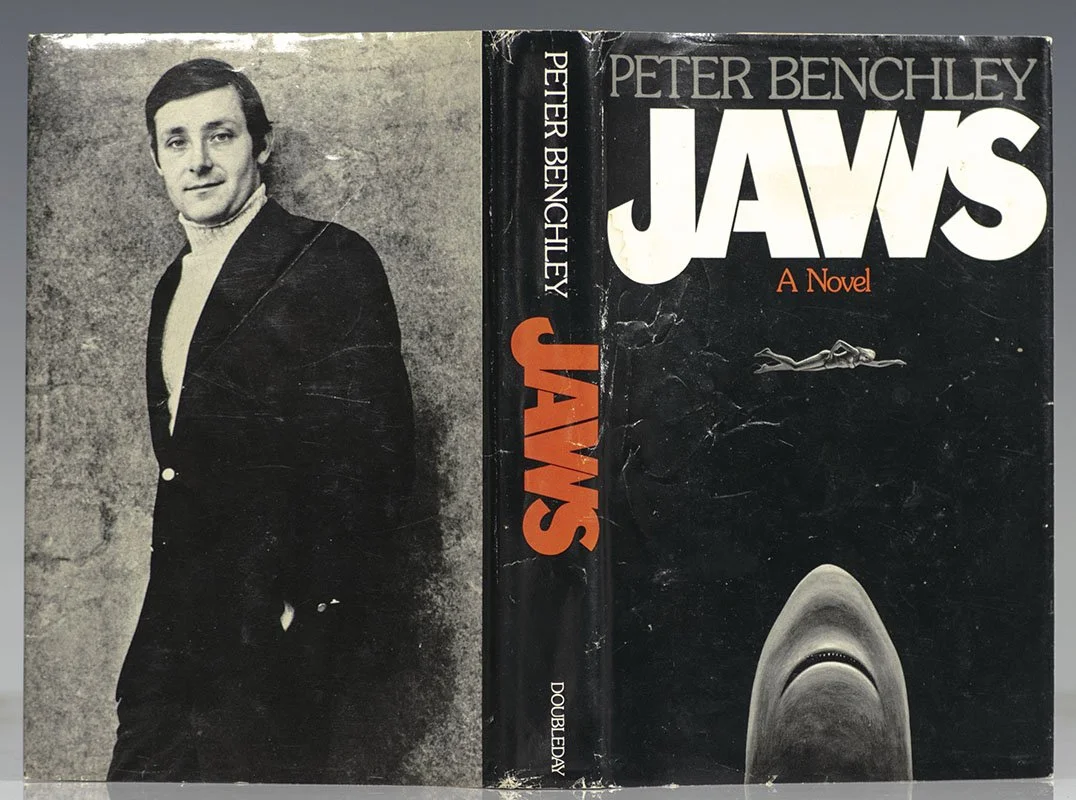

So began something of a shark obsession for me, second only to dinosaurs in those days. I read and watched whatever was available on the subject (at least on the kid-friendly level), and ordered a book on shark attacks through my school’s book service. I believe I probably read that book thirty times or more (I still have it). At one point in the book, where the Great White shark is discussed in a section describing various types of sharks that are known to attack humans, I saw a quote from some guy named Peter Benchley, whom the book referred to as “the author of Jaws.”

Wait, what?! There was a Jaws book? Somehow, I had overlooked that little detail.

Eventually, I did come across a copy of Jaws, and I immediately snatched it up and started reading. I read the attack on Chrissie Watkins at the beginning, and found it suitably horrifying. Then I flipped to the end of the book, eager to read about the climactic battle with the shark. I remember specifically looking for Brody’s line, “Smile, you son of a…” But I couldn’t find it. The shark died—that much, I could see—but I wasn’t exactly sure how. There was no tank explosion. I flipped through a little more of the book—barely recognizing anything—and put it back on the shelf, wondering, “Why would they have made it so different from the movie?” At the time, I didn’t realize that the movie was based on the novel rather than the other way around.

I tried reading Jaws again as a teenager, but didn’t get much past the discovery of Chrissie Watkins’ body on the Amity beach. I just couldn’t get into it. All I knew was that I liked the movie much better.

Fast-forward a few decades, and I’m happy to report that I’ve finally finished Peter Benchley’s novel. Verdict? I still like the movie much better. Why? Allow me to don my weather-beaten Quint cap and elucidate for you…although not in song (be thankful for that).

Warning: Major novel spoilers follow.

What the Novel Does Well

In the process of writing Jaws, Peter Benchley researched everything he could find on sharks, and his preparation shows in the finished story. The shark attacks in the novel are realistically portrayed, and to great effect. Unlike in the movie, where she gets dragged back and forth through the water, poor Chrissie Watkins is taken out quickly—in two swift strokes. The best aspect of the novel version of the attack is the tension Benchley builds into the scene. Chrissie feels a sudden swell as the shark passes beneath her, and immediately begins to panic, realizing that she’s alone and vulnerable, even though she isn’t thinking “shark” just yet. The scene is very well done and draws the reader into the story immediately.

Benchley’s version of the attack on Alex Kintner also differs significantly from what we see in Spielberg’s version. Again, the author builds tension as the shark stalks the boy, homing in on his movements. When the attack finally comes, it’s swift and devastating. Rather than dragging him down as we see in the film, the shark hits Alex from beneath like a torpedo, blasting clear of the water with the boy in its jaws, and splashes back down again before anyone can even get a good look at it. If you’ve ever seen the leaping Great Whites of “Shark Week,” flying up out of the water with seals in their mouths, that’s basically what you’ve got here. The shark of the novel is not quite as large as the shark of the film (20 feet long versus “25 – three tons of him”), but it’s still an enormous powerhouse of an animal, and exceptionally clever for a fish. Toward the end of the novel, Quint remarks that the shark attacks like none he has ever seen before.

Benchley fleshes out the town of Amity well (although it would have been more aptly named “Animosity”) and features a few characters we don’t encounter in the film, most notably Harry Meadows, editor of the local newspaper and a friend of Brody’s. As in the film, Brody’s efforts to protect the town from the shark menace are largely thwarted by Mayor Larry Vaughn and Amity’s Board of Selectmen. In the film, Vaughn is mainly concerned with saving the town’s tourism-based economy from the disaster that closing the beaches for any length of time will mean. In the novel, however, Vaughn has other concerns; namely, organized crime connections, which are uncovered by Meadows at the behest of Brody. This plot device works well in that it gives Vaughn a good bit more depth, as he more or less comes off as an idiot in the film.

The shark hunt is very different in the novel, much less dramatic, and what drama there is occurs mainly between Quint, Hooper, and Brody. The ending is also quite different. The shark basically dies of exhaustion and takes Quint down with it. This would not have worked at all for the film, especially given that Spielberg’s shark hunt (driven along by John Williams’ score) is much more dramatic than Benchley’s; but given the slower pacing of the novel, it actually works pretty well. Benchley also kills off Hooper in the shark cage scene. This is another decision that works for the novel but probably wouldn’t have gone over as well in the film. Hooper’s motivation for getting in the cage in the first place is also different here. In the film, he’s trying to find a way to kill the shark; in the novel, he just wants to get some dramatic underwater footage of a huge Great White shark.

Ellen Brody plays a much larger role in the novel than in the film, and is given a direct connection with Matt Hooper, having once dated his older brother. Stephen Spielberg famously remarked that Benchley’s characters were unlikable, and I largely agree, although I think Ellen comes off pretty well by the end—and that’s surprising given that she’s central to the novel’s worst subplot (more on that shortly). Harry Meadows is also a well-realized character, which isn’t too surprising given that he’s a newspaper editor and Peter Benchley once worked as a reporter.

What I Didn’t Like about the Novel

For me, the novel’s greatest weakness lies in its two main digressions. The first is what I call The Dysfunctional Dinner Party, where Ellen Brody hosts Matt Hooper and a few other guests in an awkward and painfully protracted scene. Unlike Roy Scheider’s largely affable Chief of Police, Benchley’s Martin Brody has two primary modes: frustrated and full-on hot-head. He picks up on the fact that Ellen is showing off for Matt Hooper and skulks back and forth between the kitchen and the living room, trying not to get drunk. It’s understandable that Brody would feel a little insecure under the circumstances—and might well make a fool of himself, as he does here—but the scene simply takes up too much space with too little consequence to the story. It reads like Benchley couldn’t quite make up his mind what to do with it, so he just kept writing.

Speaking of Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper, this leads me to the novel’s infamous adultery subplot. As I mentioned, Hooper reminds Ellen of the upper-class life and friends she left behind when she married Brody. She’s considered a good-looking woman, she’s kept herself in shape, and she begins to wonder if she still has what it takes to attract a man like Matt Hooper. She toys with the idea until it becomes an obsession, finds an excuse to meet Hooper at an out-of-town location where they’re not likely to be recognized, and the two of them get together after a “talk dirty to me scene” that left me feeling like I’d been hiding in someone’s bedroom closet. As they say today, the whole scenario is “cringeworthy,” and takes up far too much of the novel. Oddly enough, however, it leads to the only real character arc that we find in the story. Ellen instantly regrets the affair, realizing how much she loves her husband, her kids, and the life she has chosen. Martin suspects that something has happened, and even attacks Hooper at Quint’s dock, but he never forces the issue with Ellen, and I was left assuming that they both simply moved on without directly confronting the issue. The novel ends abruptly, with Brody trying to make it to shore after the deaths of Quint and the shark, so we don’t get much in the way of closure.

As much as I tried to set the film aside while going through the novel, it was impossible for me to get Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, and Robert Shaw out of my mind. Benchley’s Brody is the picture of frustration and lacks Roy Scheider’s amiable persona. Richard Dreyfuss’ Hooper is confident and sarcastic, but not arrogant, whereas Benchley’s Hooper drips with smugness to the point where he almost needs someone following behind him with a Wet Floor sign. Benchley’s Quint grew on me as the story went along, and he’s certainly the most colorful of the three shark hunters, but the absence of Robert Shaw’s quirky humor took a lot away from the character for me—to say nothing of the absence of the now-legendary Indianapolis scene. Overall, the Jaws actors eclipse the novel’s characters to the point where it was almost impossible for me to consider them on their own merits.

Final Thoughts

Benchley’s novel and Spielberg’s film represent two considerably different visions and forms of storytelling, so it’s not entirely fair to compare them directly. The film is a horror/action-adventure story compressed into 124 minutes, whereas the novel is more of a drama that deals with relationships at least as much as with the shark. That said, were it not for the film, I don’t believe the novel would have achieved any lasting notoriety. It’s bleak, at times tedious, and the characters are unappealing. Granted, I understand that Benchley’s publisher interfered with the story, demanding that certain changes be made, so the novel doesn’t entirely represent the story its author originally wanted to tell.

Peter Benchley came up with a great idea, but it was very much a diamond in the rough. It took a creative screenplay adaptation, the genius of Steven Spielberg’s direction, the inspired score of John Williams, and a trio of remarkable actors to cut and polish that rough work into the cultural gem that Jaws has since become. I’m older and (or so I hope) wiser than when I first tried reading Jaws, but even so my original instincts were right on the money: the movie is so much better.

A.J. Macready is the author of Descendent Darkness, an old-school-style vampire novel set in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. He maintains a YouTube channel—the Atlantean Archive—where he focuses on retro horror, fantasy, and science-fiction stories, movies, and shows.

Words by A.J. Macready

If you would like to write for The Daily Jaws, please visit our ‘work with us’ page

For all the latest Jaws, shark and shark movie news, follow The Daily Jaws on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.