THE JAWS SCREENPLAY: BITING CONVENTIONS

Every film begins with a screenplay.

A screenplay is your blueprint. Your map. The seed that grows the tree, or, if you will, the Holiday roast that tempts an aquatic predator.

As a screenwriter, there are a handful of films that I return to again and again, for inspiration. And of all of those films, Jaws is the template that I use the most, a simple concept treated with enough care and attention to detail, to connection, to sheer thrills, that it’s elegance and subtlety can reveal new, ingenious story beats, even more than four decades later.

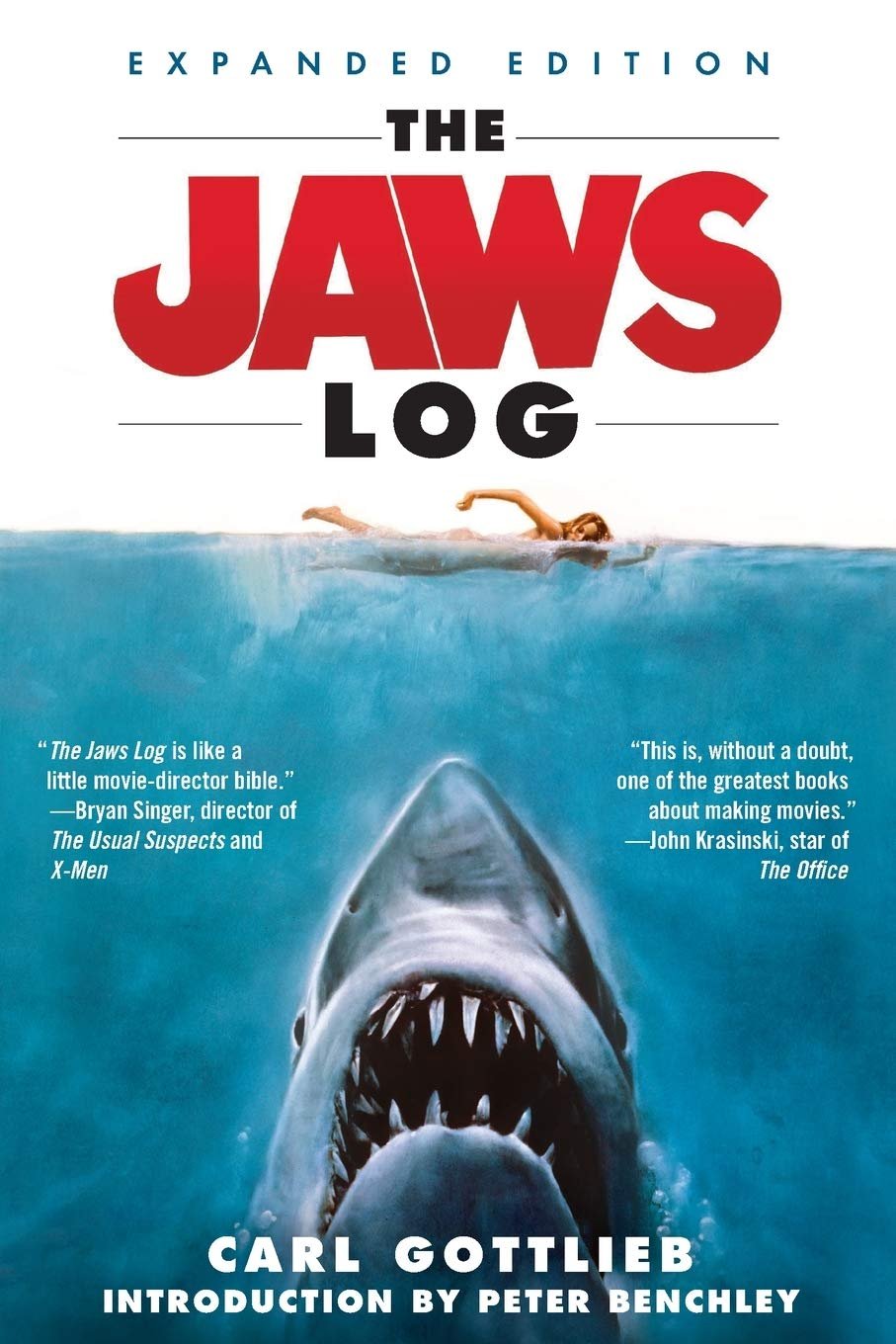

An adaptation of a bestselling novel, the screenplay went through a number of incarnations (written by the book’s author, Peter Benchley, and rewritten by Carl Gottlieb) to become the cinematic masterwork that it remains since its release.

Jaws is many things, but it harks back to a time when the Summer Blockbuster was in its infancy, and story was still the draw, rather than spectacle.

And more importantly, it’s a perfect example of that moment that every screenwriter looks for, when character and plot feed off of one and other.

There are so many examples peppered throughout the film’s script. Take Brody (Roy Scheider) unhooking the wrong rope, which introduces Hooper’s (Richard Dreyfuss) compressed air tanks that will eventually destroy the shark. These same air tanks are dismissed by Quint (Robert Shaw), in a scene that develops the tensions and dynamics of the three characters, now stuck together. But it’s doing more than that, as it is these exact air tanks that will seal Quint’s fate, causing him to lose his grip and fall into the shark’s reach. And while Hooper’s angry reaction to Brody’s clumsiness deepens their conflict, it also plants the seed that the tanks can explode, which Brody will later use to his advantage.

And very few screenplays have the guts to grind the action to a halt, at the point in act two when the pace should be accelerating, in the name of Quint’s Indianapolis monologue, but it tells us everything we need to know about his character, his humanity and, most crucially, his own fears. The notion that he would never put on a life jacket again is both haunting and dangerous, leaving Brody and Hooper under no allusions that they are with a stable Captain. It’s where the doubt creeps in to the camaraderie between the three and kicks off the third act in which it all comes to a head.

A tail.

The whole damn thing.

That this, now iconic, monologue is attributable to a collaboration between screenwriters and actor (and Robert Shaw was certainly no slouch as a writer himself), shows just how important a screenplay can be.

But also how flexible.

No script is ever truly complete until the film is released, and more often than not the screenwriter’s story will have changed radically through development, rewrites, shooting and, most crucially, editing.

There are myriad books written on the structures, disciplines and rules of screenwriting as an art form, but the reality, really is that there are no rules, only conventions. And conventions are by no means set in stone. On the contrary, they’re there to be played with.

Jaws screenwriter Carl Gottlieb (r) also played local newspaper man Harry Meadows in jaws

In that respect, you’re safer with books written by and about screenwriters, rather than books about technique, as nothing speaks clearer than experience.

For my money, William Goldman’s Adventures in the Screen Trade, or Alistair Owen’s SMOKING IN BED: CONVERSATIONS WITH BRUCE ROBINSON have taught me more about the process, as well as the business that goes hand in hand with the art, than any Save the Cat manual ever could.

And in the end, Jaws teaches any budding screenwriter that the cat, much like the dog Pipit, sometimes shouldn’t be saved.

After all, that’s just another convention.

Words by Chris Watt.

Chris is a screenwriter and script consultant, based in Scotland. A member of the WGGB and BAFTA Scotland, his feature film screenplay, THE MIRE, is currently in post- production with Apple Park Films, directed by Adam Nelson. His feature film screenplays FOLLOW UP & FR(E)IGHT were optioned by Stronghold NYC Productions in 2020, with FR(E)IGHT, directed by Steve Johnson, now in post-production.