WANT TO WRITE THE PERFECT SCREENPLAY? STUDY JAWS

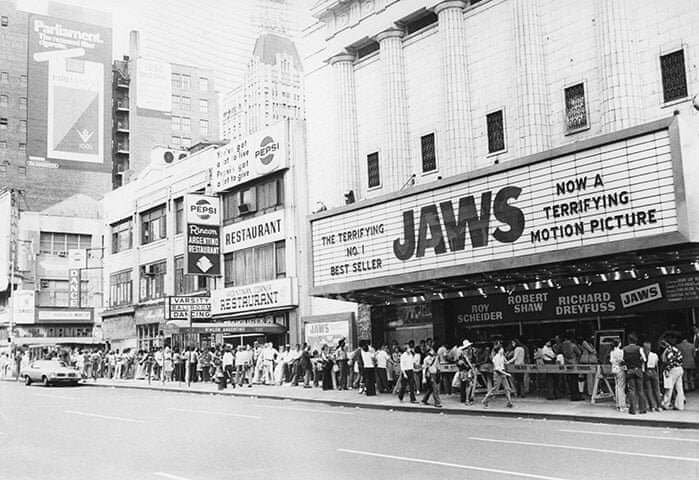

I’ve told the story many times of how I saw Jaws at the age of eight in its original 1975 theatrical release. My mother, who read the book, and wanted to see it, asked over and over if I wanted to see some kind of Disney fare. I was adamant: Jaws, lady. Take me to Jaws.

It was the first movie I saw where the audience stood and applauded. That made an impact on me. When I got out to the car I told my mother I wanted to make movies one day. It wasn’t to make something about a giant shark, I wanted people to enjoy something I made as much as all those strangers in that theater enjoyed Jaws.

Jaws never left my life. It’s been a constant. It helped change me from an introverted nerd to a John Hughes-style high school class president. Enough has been written on the film and I still say an entire filmmaking course could be taught just on the making of the film. Everything you need to know about making movies and what NOT to do, can be learned by understanding the making of Jaws.

Often overlooked is Carl Gottlieb’s script—one of the most efficient and economical screenplays put to screen. It all starts with Peter Benchley’s novel. I first read Jaws all the way through around fifth grade. I was shocked at how different the book was from the film that I saw only a year or so before.

Benchley’s novel was overloaded with characters and situations that added little to the overall narrative of a small New England community combating the impact of a shark’s rampage off their beaches. While the opening attack on Chrissie Watkins is equally chilling as the film’s opening, the book quickly goes off the rails and turns into a Peyton Place soap opera. Brody has to deal with local mob hoods, Mayor Vaughn is also in debt to the mob, Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper embark on a sexual affair, Quint just hates everybody and is a poacher of endangered animals, it gets tedious.

Carl Gottlieb jettisoned all of that nonsense. He stripped the story down to the one that Benchley once said in an interview he wanted to tell: “What if a shark came to this island and wouldn’t leave?”

This is the power behind the endurance of Jaws. The script refined Benchley’s novel into a simple “Man vs. Nature” plot that owed more than a tip of a fisherman’s cap to Moby Dick. You could go as far in saying that Jaws is in essence the first remake of Moby Dick. Obsessed captain aboard his beloved boat takes others on a harrowing vengeance boating excursion to bring down his great white nemesis.

There’s no coincidence that Quint’s death in the novel mirror’s Ahab’s as both men find themselves tied to their respective enemies and dragged into the depths. Spielberg went for the bigger Hollywood ending, and brought down the house.

Carl Gottlieb’s script moves quickly, each plot point falling into place like a cog and gear, leading us to the inevitable confrontation between man and beast. In between we have our hero, Brody, a man of the law, comedy relief in fish expert, Matt Hooper and our human antagonist, Captain Quint who is succinctly defined in the infamous chalkboard scene.

Everything you need to know about Quint is said in that simple monologue in front of Brody, Vaughn and the townsfolk. Gottlieb’s masterful use of dialogue paints his characters, shades them, without telling the audience everything in boring exposition.

The basic rule of screenwriting is “Show it don’t tell it.” Yet, Gottlieb shows us things as his dialogue tells it. The words his characters speak shade them without a heavy brush.

If Jaws were made today, the scene on the Amity ferry where Brody is confronted by Vaughn and the councilmen would go on way too long and filled with long, boring exposition as Vaughn would have to explain everything to us. A lesser writer would have Vaughn lecturing Brody on island economics, how certain businessmen would have his head, how the island wouldn’t be able to withstand the hit, how he was elected to protect Amity as well as represent— you get the idea.

Instead, Gottlieb gives Larry Vaughn just a few words that efficiently convey the severity of the situation: “You yell ‘barracuda’ everyone says “Huh? What?” You yell ‘shark’ we got a panic on our hands on The Fourth of July.”

Boom. There it is. That simple piece of dialogue tells us exactly where Mayor Vaughn stands, that Brody is up against more than the shark and exactly what’s going to come because you just damned well know leaving the beaches open is going to bring that panic on The Fourth.

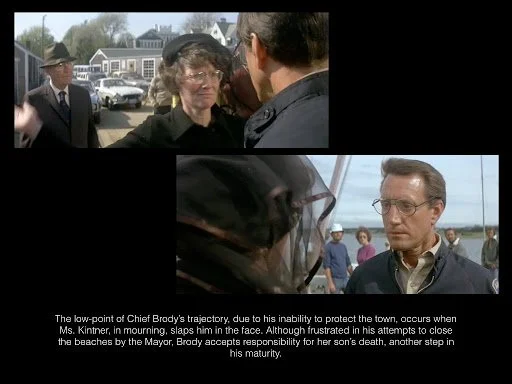

Gottlieb also knows how to tell us about their character without them saying a word. When Mrs. Kintner slaps Brody on the docks in front of everyone, Larry Vaughn stands by, silent, as she excoriates Brody, blaming him for her son’s death and Larry allows it. He doesn’t step forward to tell the truth. No, he stands there, shamed as well. When Mrs. Kintner walks away all Larry offers his chief of police is, “I’m sorry, Martin. She’s wrong.”

Again, a lesser script would’ve had Brody turning on Larry, ripping him a new ass, recounting their talk on the ferry. Brody would tell Larry that Larry was at fault, not him.

An even lesser script would’ve had Brody arrest Mrs. Kintner or get back in her face, angered at the slap and the public humiliation.

Instead, Gottlieb gives Brody a single line: “No she’s not.” As Brody walks away we understand that Vaughn hung Brody up to be wrongly blamed just like the dead Tiger Shark hanging only a few feet away.

Not only is it brilliant, efficient writing, it reaches all of us—the common people. All of us have been blamed for something we didn’t do. We get Brody because he’s a working man, trying to do right by his family and community, and in the end is the one who will stick his neck out for the entire island while the suits happily let him.

We get Brody.

We also get Matt Hooper. A simple conversation aboard Matt’s boat on their night search sums up everything we need to know about Hooper.

Martin: You rich?

Hooper: Yeah.

Martin: Yeah? How much?

Hooper: Well personally or the whole family?

Martin: Doesn't make any sense? You mean they pay a guy like you to watch sharks? Hooper: Well, uh, it doesn't make much sense for a guy who hates the water to live on an island either.

Martin: It's only an island if you look at it from the water. Hooper: That makes a lot of sense.

Less than ten simple lines and we get these two men and we find we can relate to this rich boy and his big boat. Common everyday man meets rich privilege and...we like them.

The fly in the ointment, the one to break this all up and represents the resentment and jealousy all of us have for those who get the breaks is Quint. He wastes no time summing up his contempt for Matt Hooper and a single line of dialogue tells us EXACTLY what he thinks of Hooper:

Quint: You got silly hands Mr. Hooper. Been countin’ money all your life.

Gottlieb masterfully avoids endless dialogue EXPLAINING why the shark is here. Does it really matter? Benchley’s book allowed theories of divine punishment, that somehow God was punishing Amity Island for its sins.

We get some friendly, simple dialogue at the Brody dinner table where Hooper succinctly outlines his territoriality theory. In and out. It doesn’t matter why the shark is here. Hooper explains that to Vaughn later and again, it is simplistic brilliance:

Hooper: Look the situation, is that apparently a Great White shark has staked a claim in the waters off Amity Island. And he's going to continue to feed here as long as there is food in the water.

Boom. There it is.

Remember the “Midichlorian” explanation for The Force in Star Wars Episode One: The Phantom Menace? That was so bad some people in the theater groaned around me. That labored talking and talking was as heavy as the leaden dull plot and endless dialogue so many characters in that movie spat out.

As of late movies are compelled to give tedious back stories to their villains. From Michael Myers to Jason Vorhees, writers seem to feel that if they layer the living hell out of their often mute villains with elaborate back stories, it will somehow enhance the movie.

It doesn’t.

Does the shark need a back story? Is it angry? Was it injured by fisherman far out to sea? Or...is it looking for revenge (We know how that worked out three films later)?

It’s simple: Shark comes to Amity. Shark does sharky things no good for business. Can’t ask shark top leave. Gotta kill shark.

Dammit, that’s what we paid for.

Gottlieb will repeat this simplicity in Jaws 2. No explanation is given for another shark coming along. Brody posits the revenge thing but it’s only offered as a flustered aside, not an official explanation.

I could write a literal book on the virtues of the simplicity of Carl Gotllieb’s screenplay for Jaws. I end this piece by saying to any burgeoning screenwriter reading this: “Less is more,” and read this script. See how the words are engineered, how the entire screenplay is one efficient machine.

A perfect engine, if you will.

Words by B Harrison Smith

About the author:

B Harrison Smith is the director/writer for cult hits like “Death House,” “Camp Dread” and “The Special.” He has two books coming Fall 2022 on the industry. His “This Time It’s Personal” looks at the unique phenomenon of the history of horror films seen through the theatrical experience. He is collaborating with writer/director Tommy Lee Wallace on a definitive account on the making of Wallace’s “Halloween III: Season of the Witch.”

His upcoming monster movie, “Where The Scary Things Are” will be released this year from Lionsgate/Grindstone.