HOW WE CAME TO FEAR SHARKS... LONG BEFORE 'JAWS'

When did sharks and the fear of shark attacks enter our psyche?

Jaws, right? I got that beat. Sharks, they've been around for millions of years, even Chief Brody knows that.

Thanks to the likes of Shark Week on Discovery and SharkFest on National Geographic - and hey, The Daily Jaws - fins are never far from our screens or thoughts.

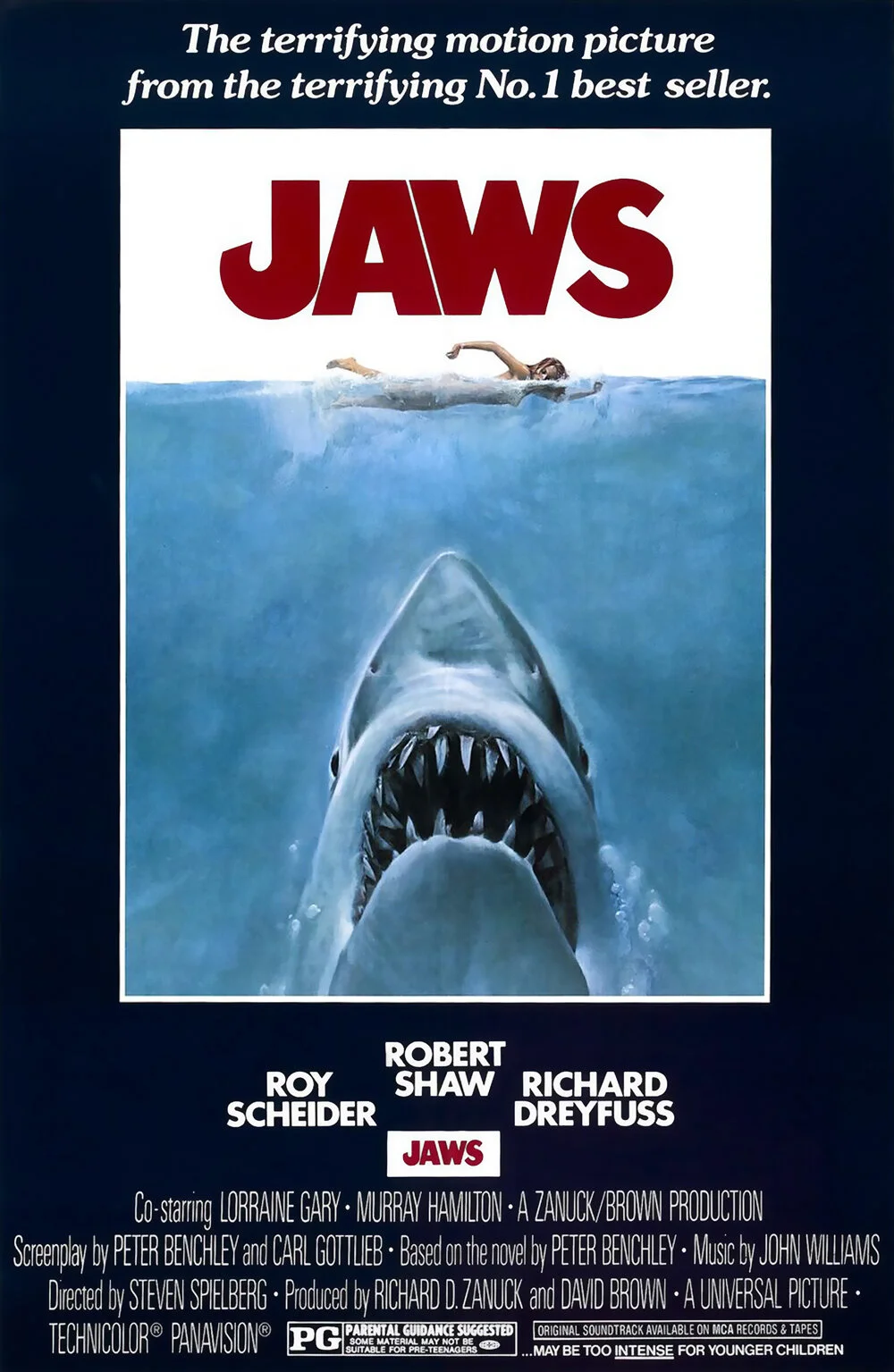

And almost 50 years ago the shark became a permanent fixture in popular culture thanks to Jaws, first the book by Peter Benchley and then the blockbusting film by Steven Spielberg. In fact it became the first film to cross the then magic $100 million barrier in the US.

In either format, the great white did as it would in its natural habitat, it devoured the competition.

Of course, sharks and our fascination or fear of them didn't begin with Jaws when it was published in 1974. They've always been there swimming below the surface, but at several key points on recent history that dorsal fin appeared and its rows of teeth grabbed our attention, and wouldn't let go.

Jaws may have been the biggest wave culturally, but there were two earlier waves in the 20th century that cemented the shark as apex predator and as a maneater in our consciousness.

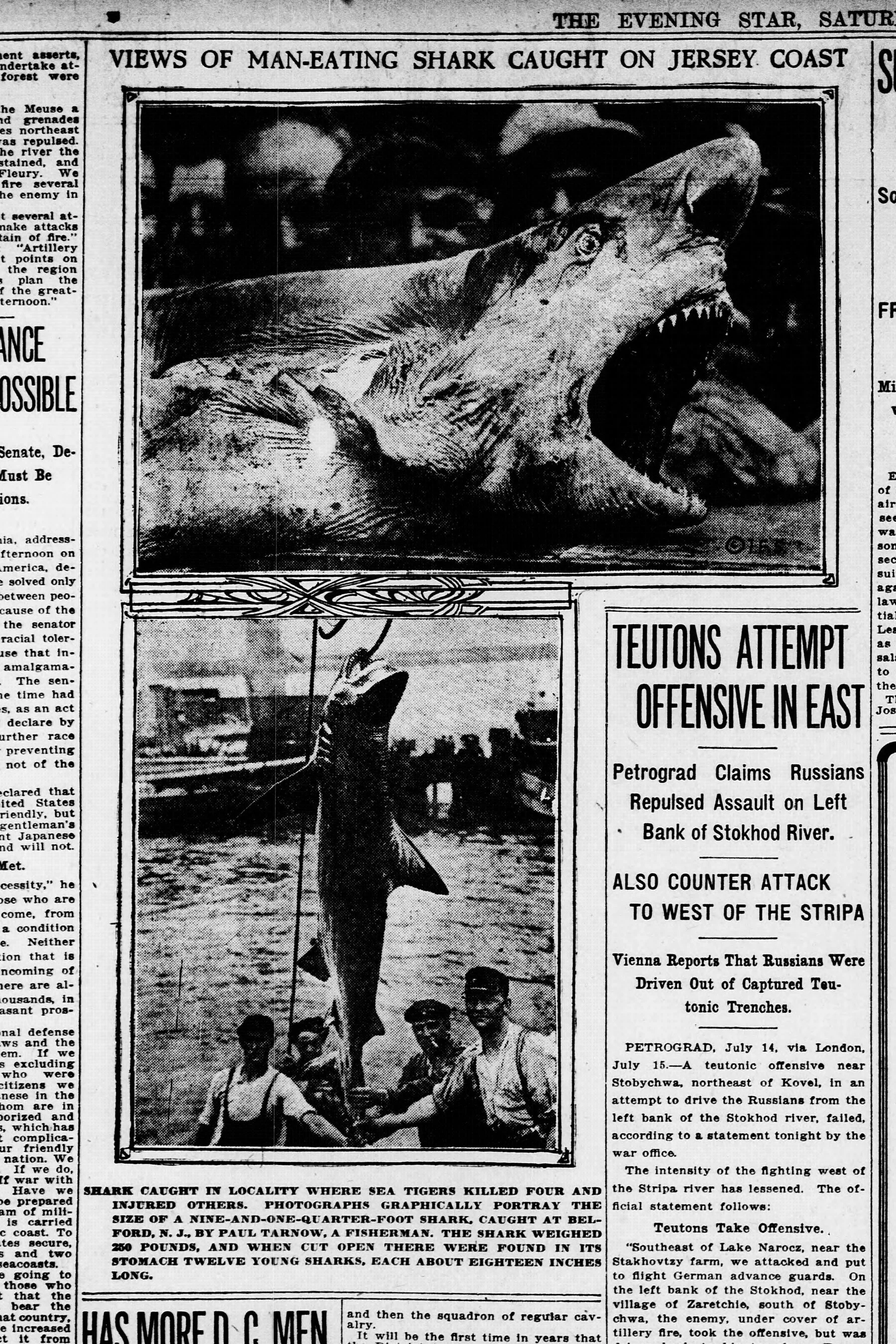

That first time was in July 1916, and it struck out of nowhere. Much like the first shark attack that fateful day on the Jersey beach on Charles Vansant. At the end of the spate of almost two weeks of terror there were four people dead and one injured.

It even knocked the events of World War One from the front of newspapers in the US, and was discussed by the President. The attacks were a watershed moment for sharks, as until then scientists believed they wouldn't come close to humans, and certainly weren't dangerous.

The attacks - which took place both in the sea and the local freshwater creek - ceased as soon as they started, with the culprit either suspected as a great white or a bull shark. Or perhaps even both.

You can read more about those 12 days of terror here: The First Summer of the Shark

If those events that took place whilst World War One raged raised our fear level of sharks, it was events during World War Two that solidified it.

Soldiers and civilians who found themselves torpedoed, in sinking ships or in planes that have crashed in the ocean were in hot water. Sharks are scavengers and often in the vast open sea they will take every opportunity when it floats their way, and that includes the above.

That thrashing in the water like a distressed animal, the blood of the injured, dead bodies, oil and vibrations are like ringing the dinnerbell to sharks. They aren't people to them, it's a welcome food source that's appeared in their domain.

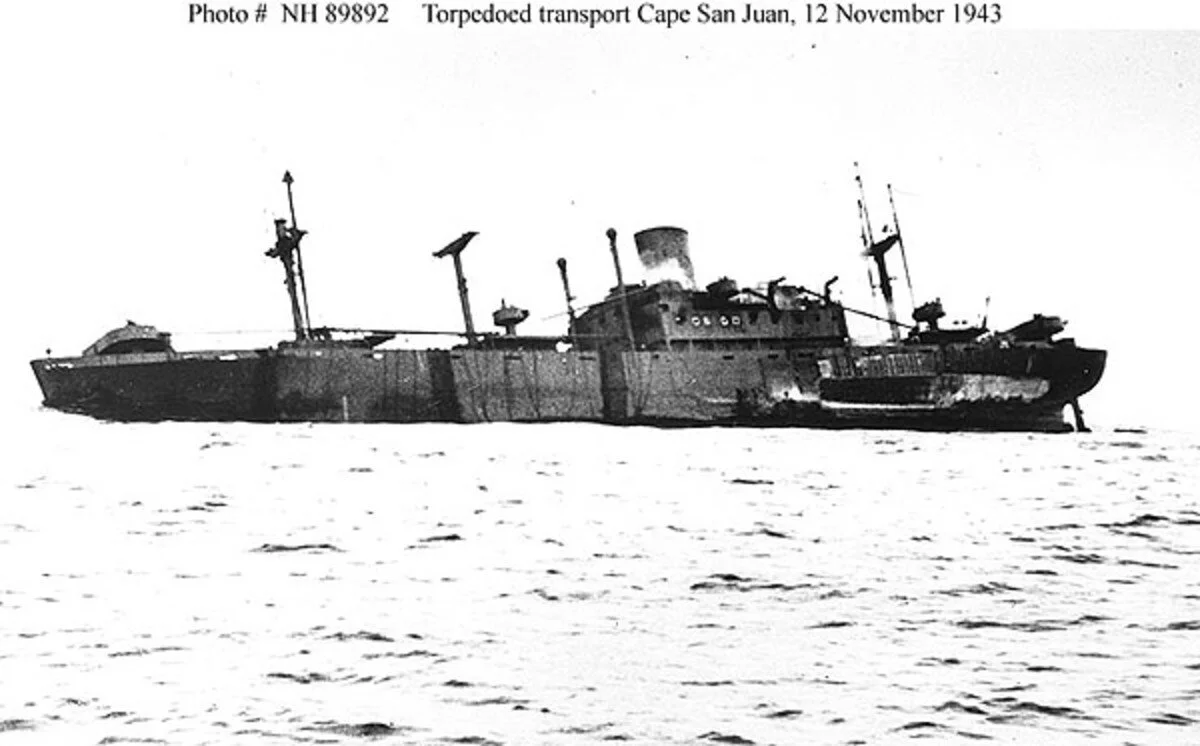

That fate befell many of those on board the Cape San Juan, a 6711-ton US freighter and troop transport ship. On November 12, 1943 it was torpedoed by Japanese submarine in the Pacific Ocean near the Fiji Islands.

It's said sharks were even attacking as the rescuers were trying to pull them out of the water. An estimated hundreds perished to the sharks.

The Cape San Juan, torpedoed in November 1943.

Just under a year earlier, the British troopship Nova Scotia was sunk by a torpedo off Cape St. Lucia, South Africa. Of the 750 troops who died, it is estimated a quarter were taken by oceanic whitetip sharks.

However, the most deadly and most infamous shark attack episode ever, is that of the USS Indianapolis.

Quint, from Jaws, may never have been on the ship, it's mission to deliver the near bomb to be dropped on Hiroroshima, but its mission, its sinking and those sharks, were very real.

And those sharks were oceanic whitetips, they were always in the water, it wasn't them that sank the ship with torpedoes , but over those days that followed, it would become known as the worst shark attack in history.

Ocean whitetips are often known as being sharks that attend shipwrecks, and this was no different. They'd be attracted by the dead, the dying, the remnants of the ship which sank in just 12 minutes, and by the commotion and confusion in the water.

Survivors of the USS Indianapolis are taken to medical aid on the island of Guam

Not that the sharks knew there were humans, they were just a feeding opportunity in the the open ocean, in the wrong place at the wrong time. The open ocean is essentially an ocean “desert”, where meals are few and far between, so this inquisitive shark will bump and access any potential source of food.

Being an open ocean shark - so you won't find them coming to a beach near you - you'll have to sink in a boat or crash in a plane in their domain. Which plenty did during World War 2, and so that reputation has stuck.

Both the 1916 attacks and those from the Second World War, in the form of the sinking of the Indianapolis, were significant shark hysteria waves referenced in Jaws, doffing its cap to the other seminal shark moments of the 20th century.

The 1916 shark attacks are mentioned by Matt Hooper and Chief Brody to Mayor Vaughn outside the defaced Amity Regatta billboard.

The second isn't seen, it is heard. It is of course the mighty USS Indianapolis speech by Quint, arguably the most powerful moment in the film and perhaps cinemas greatest monologue.

You can still hear a pin drop whenever it is screened, we become Hooper and Brody, hanging on his every word.

FURTHER READING: 75 Years On: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis

We may as well be in those waters, and that is the power of Jaws, and our ongoing fascination with all things shark.

Jaws opens the door and acts as a real springboard to not just the history of man and sharks, but also helps influence its future and our understanding of these amazing creatures, by encouraging people into careers researching and saving sharks.

Something Jaws author, Peter Benchley, would have undoubtedly approved of.

Words by Dean Newman