The First Summer of the Shark

Noises from the beach are in ear shot between strokes in the water, but Charles Vansant swims alone. Stroke after stroke he glides further away from the beach, except he isn't alone.

Something is following him unseen through the water, honing in on the kicks of his legs and the scoops of his arms. That something is a shark.

Charles Van Sant

Vansant had arrived on the coast that very day, July 1st, travelling from Philadelphia with his dad and sister. She, along with other beach goers bore witness to the attack as the water turned crimson.

A lifeguard swam out to save him and free him from whatever was attacking him, the lifeguard said something had hold of Vansant's leg, but that he suddenly appeared lighter when out of the grip of the shark.

Sensing struggling in the water, the shark attacked again and again. Vansant never gave up his fight, but neither did the shark.

Despite being taken to shore, Vansant had suffered horrific trauma and blood loss, going into shock he died on the floor of the hotel lobby that he was due to stay in. His dad, a doctor, couldn't save him and he died of extreme blood loss at 6.45pm that evening.

It is the year 1916 and Charles Vansant, 25, had just become the first recorded shark attack death in the US, welcome to Jersey Shore.

At that time though, no one was clear what had attacked the man, sharks weren't thought to be especially dangerous to people and recreational swimming was at the beginning of its boom. The story only appeared in a few column inches on page 18 of the New York Times, hidden, just like the shark.

But soon events would spiral, the death toll would rise and the details of that summer would even knock The Great War from the front pages. Long before the fictitious events that occurred on Amity Island in Jaws, this would become the first ever summer of the shark.

Man thought he was safe in the cool waters of New Jersey, man was wrong. And as the summer temperatures rose, so did the numbers of people headed to the New Jersey coast to cool off from the 4th of July heatwave. And as the numbers of people in the water increased, so did the chance of another shark attack.

Charles Bruder grave

The first attack took place in Beach Haven; the next resort further up the coast was Spring Lake, whose cooling waters would boil with a ferocious second shark attack. Charles Bruder, 27, a bell hop at a local hotel, swam hundreds of metres away from the crowded beach and into razor sharp toothed oblivion.

Once again, the attack was witnessed from the beach, this time a group of men, including a lifeguard, took out a rowing boat to save Bruder. As the men rowed towards the blood they saw Bruder and pulled him in the boat, it was then they saw that his lower legs had been completely bitten off. By the time they reached shore Bruder had already died.

Joseph Dunn

Had a Great White strayed into the previously safe waters? At that point in history, that was the only shark people knew could be capable of such carnage, such death. It was the only shark people meant when they used the term maneater.

And now shark hysteria was starting to spread across the coast and onto the front pages of newspapers. The question people were asking wasn't will the shark attack again? It was where?

To some, shark attack seemed fanciful; they claimed it was perhaps a sea turtle or mackerel, others even a bizarre German plot on account of a U boat supposedly having been spotted off the coast that was herding sharks to shore.

With hotel bookings down and cancellations rife, some resorts hired men with guns to patrol the beaches and erected wire nets in the water to keep any predator out.

Real, or imagined, shark sightings spiked. Every shadow a shark, every ripple a fin breaking the water. Just like in Jaws, patrol boats were sent out with men with guns to kill the man eating shark before it had chance to kill again. As a result, many sharks were caught and killed, but when they were cut open all they contained were fish. No human remains.

Whilst the focus had been on the beaches, it would soon move to Matawan Creek, a freshwater tidal inlet that had long been a popular spot for a dip. After almost a week of no attacks, this is where man and shark were set to meet once again on July 12th.

As the shark headed to the creek so did brothers, Joseph and Michael Dunn, headed in from New York which was just 50 kms away. The pair knew never to swim in the sea, so stuck to the safe haven of the creek. Earlier that day a Captain Cottrell had spotted a fin moving up river, he knew it was a large shark.

He tried to warn the town, but no one would heed the retired sea captain’s warning. Knowing that it was a hot day and that there would be boys swimming in the creek he raced to his boat to warn them in person. He just hoped that he could reach them in time.

At around 1pm the Dunn brothers and one of their friends dive-bombed into the water, alerting the shark to their presence.

Elsewhere on the Creek, Albert O'Hara was fishing, not that he'd got any bites that day. He was soon joined by his best friend, Lester Stillwell, aged 11, who convinced him to go swimming with a few friends at Wyckoff Dock. They were around 1 km away from where the Dunn brothers were cooling off in the water at the Brickworks Dock. And it was here the shark would reach first...but swim past, instead honing in on Wyckoff Dock.

O'Hara felt something rub past him in the water, then not moments after shouting “watch me float, fellas!” young Lester Stillwell was grabbed by the shark and "shaken like a dog with a rat". And then, he was gone. Unable to do anything the panicked boys raced from the Dock to raise the alarm in town.

Tailor, Stanley Fisher, heard the boys’ commotion as they reached Matawan. Along with other men from the town they urgently headed down to where Lester was last seen. By now it was 3pm, and most of the town where there to help look for Lester, included his frantic parents.

Stanley was one of the men who dived into the Creek to help recover Lester's still missing body. They knew he was dead but still didn't think he'd been attacked by a shark, a known epileptic, they'd figured he'd most likely had a fit and drowned. The least they could do was to retrieve the body for his distraught mum and dad.

11 year old shark attack victim Lester Stillwell’s grave

Stanley took one last dive to try and locate the boy, this time heading deeper in the water, and deeper into trouble. He found Stillwell, but the shark was also there, still feeding on the young boy's body. Instinctively, Fisher pounded the shark in an attempt to free the remains of the boy, and he was able to bring Lester to the surface.

The Shark followed though, this time taking Stanley, eating him in front of a shocked town. Stanley managed to repel the shark once more, pounding him with a broken oar. At last he was free and able to make his escape and head to the safety of the Creek bank. Fisher's right leg was ripped open from hip to knee, blood spilling all over the dock.

Stanley Fisher’s grave

The nearest hospital was 50 km away and 24 year old Fisher was hurriedly put onto a train to speed the journey - roads being too bumpy and taking too long. The only tunnel he entered on that train was one of light, dying from the huge blood loss from his gaping wound.

Having killed two people in Matawan Creek and two on the beaches, that was four victims, but as it headed back to sea this shark was far from done. Having seemingly evaded the shark first time round Michael Dunn, his younger brother Joseph and their friend would not be so fortunate a second time. The threesome had no idea of the events that had unfolded just a single kilometre away and were still enjoying the water.

Then, they heard a boat engine and a man waving and shouting, it was Captain Cottrell warning them of a shark. He was still a way off, but soon they realised he wasn't shouting at them for swimming off the private dock but warning them of a shark in the water. Cottrell was just glad that he'd reached another group of boys who would now get to the Safety of dry land.

Except not all of them did. The boys started making their way to the side to get out when cruelly Joseph was pulled under just as he was reaching the ladder to safety. His older brother, Michael, fished in the now bloody water for his brother and managed to grab his arm, both boys pulling with all their might. An unconscious Joseph was brought to dock, just as Captain Cottrell pulled up alongside. They headed back up on the river on the boat.

Joseph was the only victim to make it to hospital, but was still in a critical condition, eventually leaving hospital two months after he was attacked. The only attack victim to survive.

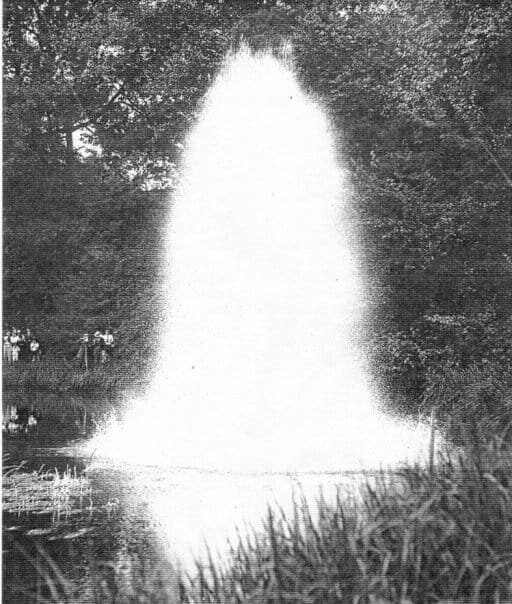

That evening and into the night, the Creek erupted into life, full of exploding dynamite and riddled with bullets as armed men and women lined the Creek in an attempt to kill the monster that lurked beneath the surface. Any ripple in the water was assassinated. Furthermore, the town put a $100 bounty on the shark, that's over $2,350 today.

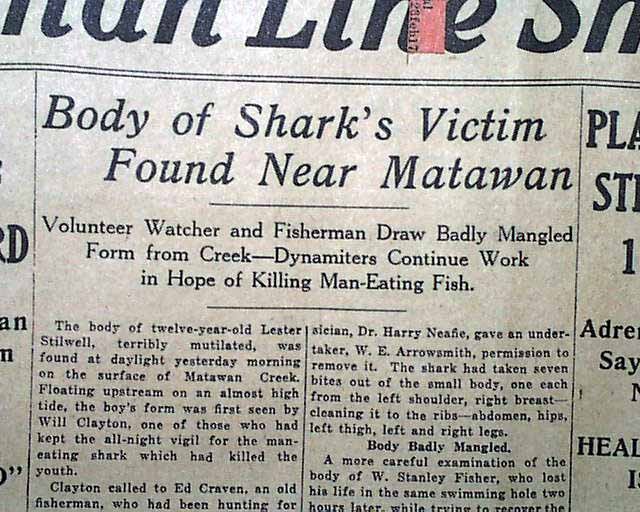

The only thing that rose to the surface was the body of Lester Stillwell, two days after he had been killed. The shark, escaped back to the open water. Open water that soon ran red again, but this time with chum and the blood of hundreds of slaughtered sharks in an effort to find the killer and human remains. It was war on sharks.

Two days later, on July 14th, if anyone was going to need a bigger boat it was Michael Schleisser, a lion tamer for Barnum and Bailey no less. In his net he had caught a large shark; it threatened to pull him and the boat under. With a broken oar on his boat he repeatedly hit it, again and again and again, until it struggled no more. And his other job? A taxidermy man. Quint would be proud.

On July 15th the dead of Matawan were laid to rest, that same day in New York, Schleisser began cutting into the shark, he would eventually remove seven kilograms of flesh that wasn't fish, and then human bones. A shin bone of a boy and a section of a man's rib.

It was a juvenile Great White, and after that there were no more attacks. That doesn't mean it was the shark, and debate rages over whether it was a Great White or a Bull Shark that had caused such terror and panic that summer.

It has even been suggested that it was a Great White responsible for the sea attacks and a Bull Shark for the ones in the Creek.

We know Bull Sharks can swim from salt to fresh water with ease, less so for Great Whites. But it was a full moon during that period, which meant the tide was higher and salt water content of the Creek was higher than normal. High enough to sustain a Great White for several days.

Since those fateful events of 1916, there has never been another reported shark attack in Matawan Creek. Swimmers again fill the cooling water, still considered a safe haven. For now.

The summer of the shark would return in 1975, this time on the big screen, with Jaws. The Steven Spielberg thriller even referencing the attacks when Brody and Hooper are talking to Mayor Vaughn in front of the defaced Amity Island Welcomes You sign.

Dynamite is detonated in the lake in an attempt to kill the shark.

It, alongside the real life Indianapolis sinking, becoming permanently a part of Jaws and shark history when people delve deeper beneath the surface of the film.