JAWS: A UNIQUELY ENVIRONMENTAL FILM

Since it swam onto movie screens and our hearts 46 years ago, most of us have experienced and loved Jaws as a pop culture phenomenon. It’s shocks and thrills, it’s indomitable sense of adventure, it’s endlessly quotable quips and its endearing characters have enriched our lives in countless ways. But there’s another way of thinking about Jaws that shows how truly deep and thought-provoking an experience it is. Although few remember it as such, Jaws is one of the most intensely environmental movies ever made, and could be called one of the true pillars of modern American cinema about the environment.

I’m the producer and co-host of Green Screen, “the environmental movie podcast,” where we watch, analyze and discuss popular movies about the environment or in which nature plays a major role. This week we just released our episode on Jaws to honor both the anniversary of its release and the upcoming 4th of July holiday with which it’s associated. Far from it being “out there” to discuss Jaws in an environmental context, we’ve found that few other movies we’ve ever done on the podcast spotlight the natural environment in such a direct way. If you’re used to thinking that only films like Erin Brockovich or The China Syndrome are really “environmental films,” then a re-think of Jaws might be in order.

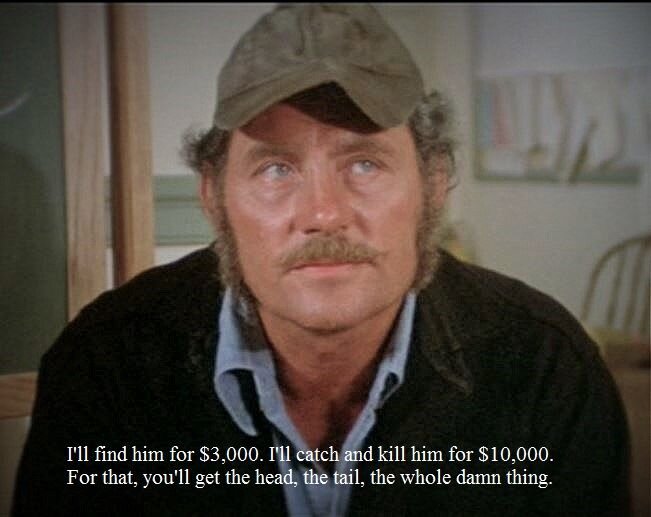

The whole concept of Jaws is environmental. The villain of the piece—the shark—is a rare example of an antagonist in a film completely divorced from human agency. As Hooper observes, “All this machine does is swim, and eat, and make little sharks. And that’s all!” The threat comes solely and purely from the natural environment. Rare among films that feature environmental themes, the issue of human complicity in bringing on the environmental threat never comes up, as it does in, say, James Cameron’s Aliens, where human intrusion into the habitat of a hostile species is the trigger for its aggression. The characters in Jaws, even Hooper, the book-learned expert, and Quint, the fisherman with a deep grudge, seek to deal with the shark’s environmental threat on its own terms. Only Brody seems to ascribe anything close to human-like motivations to the shark, becoming motivated to destroy it only when it goes after his son.

On the other hand, human agency is very much a part of why Jaws’s human characters perceive the shark as a threat. It’s not just that the shark is eating people randomly, which is certainly bad enough, as the anguish of the grieving Mrs. Kintner demonstrates. The issue is that the shark threatens the economic basis of the town, which is based mainly on human use and enjoyment of the natural environment. Economically, Amity is worth nothing unless you can swim there in the summer; if you can’t, people who want to do that, the mayor tells us, will simply go somewhere else, like the Hamptons. “You going to play it cheap?” Quint taunts. “Or be on welfare the whole winter?” In this way the purely environmental threat translates into the possibility of real suffering for Amity’s human inhabitants, in specifically economic and social terms. That’s a translation that few other “environmental films” manage to make so deftly.

As many astute Jaws fans may know, the story of the book and film is based on a real event, a series of fatal shark attacks on the New Jersey coast in July 1916, in which a great white was suspected as the culprit. We discuss this incident at length in our podcast, but our discussion led us to a lot of thought-provoking tangents. Was human activity responsible, perhaps indirectly, for bringing one or more sharks into conflict with humans that summer?

At the time, a newspaper correspondent suggested that German U-boats lurking off the U.S. coast—World War I was going on at the time—might have somehow stirred up shark populations. That specific suggestion seems absurd, but it is certainly true that shipping lanes and fishing habits changed dramatically as a result of the war, even before the United States became directly involved. Something as simple as a coastal factory dumping some kind of trash off their pier that they hadn’t been doing before might have altered the complex ecological equation of how Atlantic sharks behaved off the coast of New Jersey. We can never know for sure, but these are the sort of questions that make environmental history relevant and interesting.

Jaws is definitely an entertaining film and an unforgettable thrill ride. All the reasons we love it are what make it worth revisiting again and again. But there’s so much under the surface that’s also worth thinking about. The environmental aspects of Jaws are just one element of the extraordinary richness of the film and the phenomenon.

By Sean Munger, Ph.D. historian / host of Green Screen podcast.

Follow Green Screen Podcast and Sean Munger on Twitter. Learn more about the Green Screen Podcast online.