JAWS: THE FILM AND THE LEGACY

For a film that is almost 50 years old, Jaws still continues to deliver to audiences old and new alike. Jaws is firmly apex predator when it comes to any other shark film, so why is this film about the White Shark still so great?

As a film, it is as if Steven Spielberg and the combined talents of composer John Williams, editor Verna Fields, cinematographer Bill Butler, camera operator Michael Chapman, production designer Joe Alves and co-screenwriters Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb, have built us the perfect beast of a film.

To paraphrase Matt Hooper, played by Richard Dreyfuss, “It’s a perfect engine, a box office eating machine.”

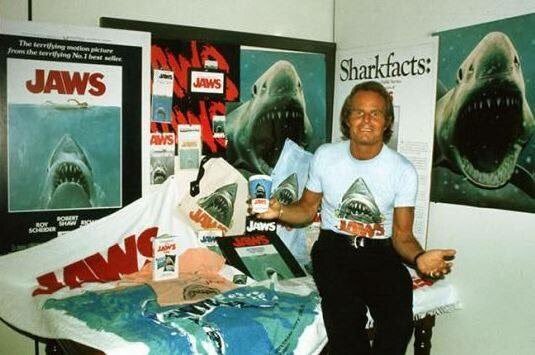

Fittingly, in a film where a shark that eats people, it had a killer marketing campaign from those nice people at Universal. That campaign included 30 second TV spots across the main channels and a now classic trailer, featuring the dulcet tones of Percy Rodriguez on voiceover duties.

And although Universal had gone wide on its release (normally a film would creep out across the country and not be released all at once as they are commonplace today). Its smart money was on Airport 1975 and The Hindenburg; the latter crashed and burned at the box office, just like its actual namesake.

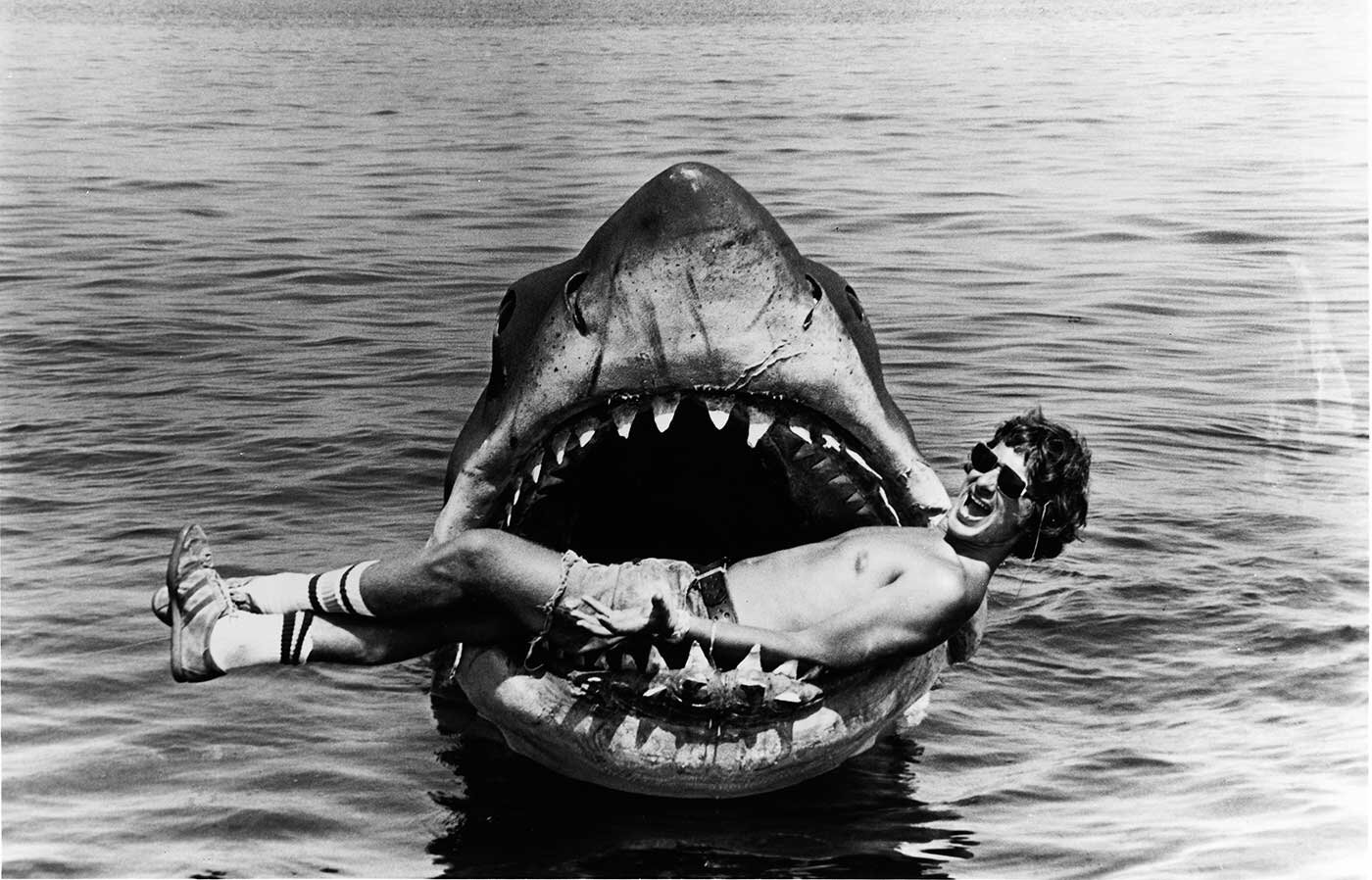

It went over production schedule, over budget and the mechanical shark, fondly nicknamed Bruce after director Steven Spielberg’s lawyer, often didn’t work. The film should never have worked, but all of this extra time meant the film matured, like a fine wine (red and white of course), to become the classic that we have today.

By the end of its initial cinematic run, it is estimated that an astonishing 67 million Americans saw it upon release.

We all know the story, Amity Island, a seaside town off Long Island is getting ready for the summer season (the best they’ve ever had), but it could have never been ready for the murderous shadow of a Great White shark.

As the victims continue to wash up, the town hire a grizzled fisherman to catch it and kill it. Joining him at sea are a marine biologist and the town’s chief of police. It’s sink or swim for the thrust together threesome as they fight against the elements, against each other and against the shark.

Jaws still packs a punch (or should that be bite radius) of a juggernaut. The opening night Chrissie attack sequence is still uncomfortable, her nakedness making you almost feel voyeur like – making it even closer akin to the shower scene it Psycho in that respect – right up until that moment of impact that’s like a train, when the John Williams score and sound effects really kick into high gear. It’s the perfect opener for a movie.

It effectively sets the shark up as a Jack the Ripper like monster. The noise, the screams and the music all blend to still create a sense of dread in the pit of your stomach. It’s also one of the most iconic, and oft-imitated, poster images ever. She was the first…

However, it’s not the 25 foot shark; all three tons of it, that dominates the film though, each and every piece of the film he is in is dominated by Robert Shaw as Quint. Scheider and Dreyfuss are no slouches for sure and the way the threesome ping off each other is a joy to behold, the script coupled with the beauty of the extra rehearsal time due to operating problems with the shark et al.

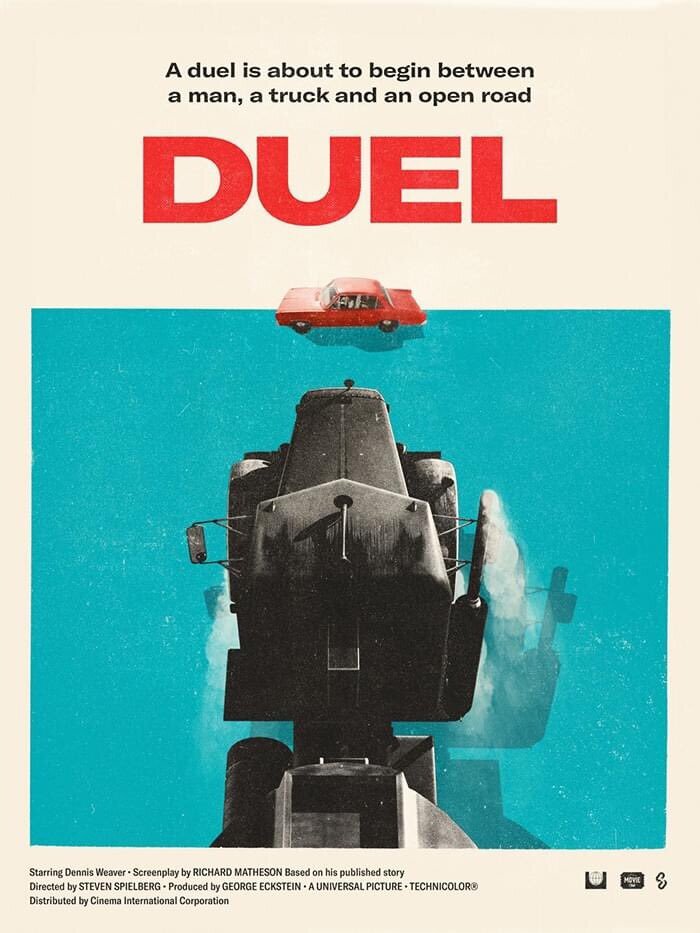

At the time the Spielberg felt that the film was too similar to the man versus (mechanical) beast of Duel (1971). He wasn’t too worried about the lorry and shark having the same dinosaur death cry though, one as it lurches over a cliff, the other as its carcass sinks to the bottom of the sea. Spielberg felt both had a kinship of sorts – both leviathans targeting everyman.

The original schedule of 55 days tripled due to the problems of filming on location, not so much the filming at Martha’s Vineyard, which doubled as the quaint Amity Island, but more the filming at sea, which almost left the whole production at sea. Previously most movies set at sea were filmed in giant tanks with a pre-filmed backdrop but being on a real sea, on a real boat it made the experience that much more successful.

The 12 hour days were not wholly productive as only four were devoted to actual filming, due to the poor weather and the not wholly co-operative shark (it sank on its first test and practically exploded on its second), but in the end these were the elements that helped make the film the success it was.

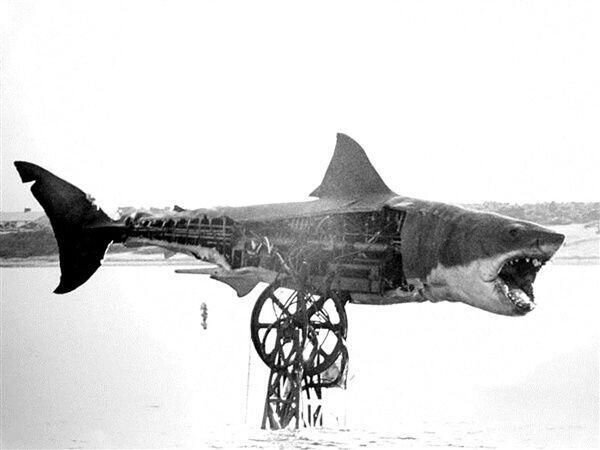

Initially the producers, Richard Zanuck and David Brown, thought(!) that they might be able to hire a man to train a Great White to perform a few simple tricks and do the rest with miniatures. Thankfully this route was not pursued and it soon became very clear that there was only one man who could help make this monster fish a reality, the retired Bob Mattey, who created the giant squid for Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea some 20 years earlier.

Due to his eyes often being crossed and his mouth not closing, the shark was not working in the salt water as was hoped. This, however, proved to be Spielberg’s masterstroke as he had to be more inventive and hide the shark behind the camera for as long as possible.

Instead, its presence suggested by twisting camerawork and the now unmistakable primeval music composed by John Williams, thus allowing the audience’s mind to create the horror of the shark, all 20, I mean 25 feet of him. And of course those rather cannily placed yellow barrels!

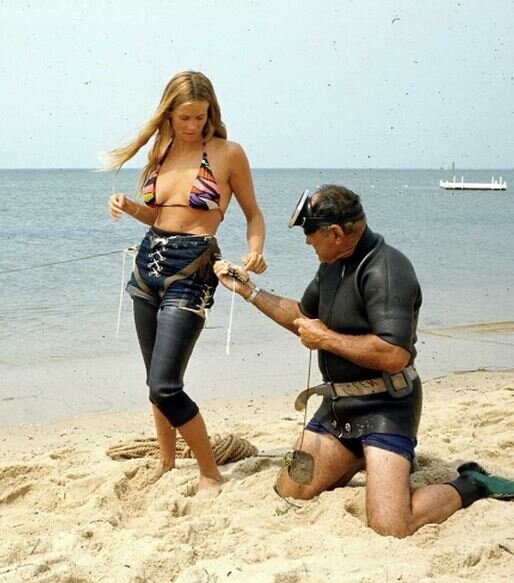

No matter how well the shark performed or how well it was hidden when it didn’t the filmmakers knew that the audience would need to see real sharks, and that is exactly what they got with amazing footage from Australian husband and wife diving team, Ron and Valerie Taylor.

Thankfully Great Whites do not grow to 25 feet in length, so to make the shark look larger for the Hooper cage dive a smaller cage and midget were used to get some spectacular footage.

But the best was yet to come when the shark destroyed the cage and almost the boat, thankfully the pint size stuntman, Carl Rizzo, was not in it at the time and after seeing the ‘attack’ on the boat promptly locked himself in the toilet. The footage remains in the film, which effectively meant the shark helped rewrite the book and ensure the survival of Richard Dreyfuss’ character.

Peter Benchley, and old pal of Spielberg, Carl Gottlieb, are listed as the screenwriters of the project but beneath the surface of the credits it is revealed that several different people helped stamp their authority on the project.

Benchley had two passes at the script and then the Pulitzer winning playwright (and scuba diver), Howard Sackler, was brought in to beef up the script. One of his greatest additions was the Quint USS Indianapolis monologue.

This one moment, more than any other, has been the one that has become fabled in who should take the credit for the powerful moment when Robert Shaw’s character retells his World War 2 shark encounter. Future Apocalypse Now and Conan scribe, John Milius, had a crack at it with Shaw himself, an accomplished playwright, also gave it a polish and honed it to the perfection you see on scream, depending on whose tale you listen to of course.

FURTHER READING: The Writers Who Brought Jaws To The Screen

The great thing about the hours of waiting to film meant that the main actors (Scheider, Dreyfuss and Shaw) all got to hone their characters, got to know each other and also got to rework their dialogue with co-screenwriter, Gottlieb (who also played opposite Mayor of Shark City, Murray Hamilton) who often updated dialogue only 24 hours before the shoot, which perhaps goes someway to explaining why these three characters and their words and every nuance is so spot on and crisp over 40 years later.

There’s often a debate – even within our own pages on social media – as to what genre Jaws falls into. Some class it as horror, others action. But truth be told, it fits into several camps, and that is part of its beauty and lasting and wide appeal. It’s got action, drama, adventure, horror, thriller and chum buckets of humour. It has something for everyone.

And as you mature, like Quint’s pretty good stuff, the way you watch and experience Jaws also matures. When you were younger you might have been there for the shark attacks and the shark – who only has four minutes of screen time – but now you watch it for the people, the characters and the wonderfully on point dialogue. Nothing is wasted, everything is there for a reason and all of it continues to deliver and delight, which is why Jaws only just keeps getting better with each subsequent viewing.

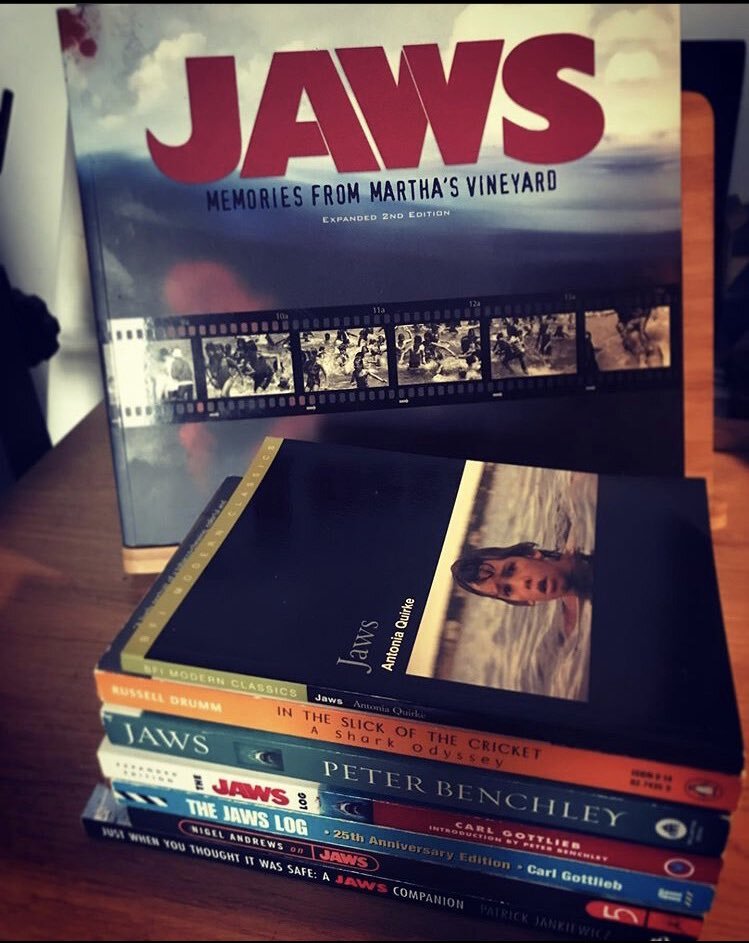

There is an aura (no, not Aurora) around the film that still holds its magic, a film whose making of is almost as legendary as that of the final product itself, thanks in no small part to the still essential behind the scenes read that is The Jaws Log by Carl Gottlieb.

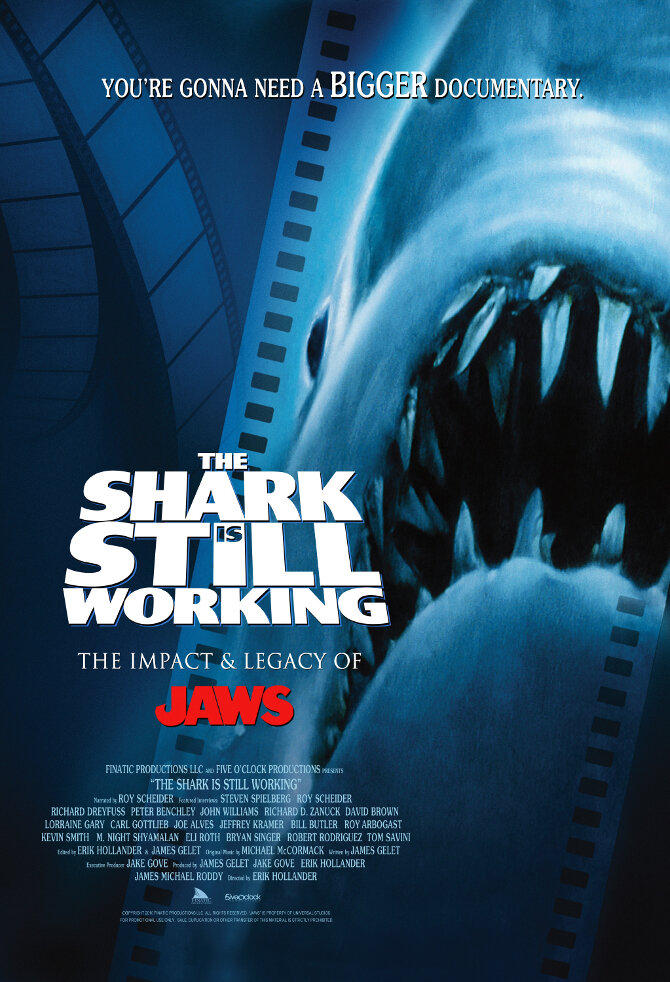

That legendary status has been further cemented by The Shark Is Still Working documentary, the simply stunning The Shark Is Broken stage play by the son of Robert Shaw himself, Ian Shaw, and there’s even a forthcoming Jaws musical based on Gottlieb’s book. Although the shark from Jaws is dead (spoiler alert, Chief Brody shot an oxygen tank it its mouth blowing it to kingdom come) it has in many ways never been more alive.

The filming schedule of Jaws ballooned from 55 days to 159 days, in what could have sunk the production and the career of Spielberg. Instead it made them, and Hollywood history and the summer blockbuster was born.

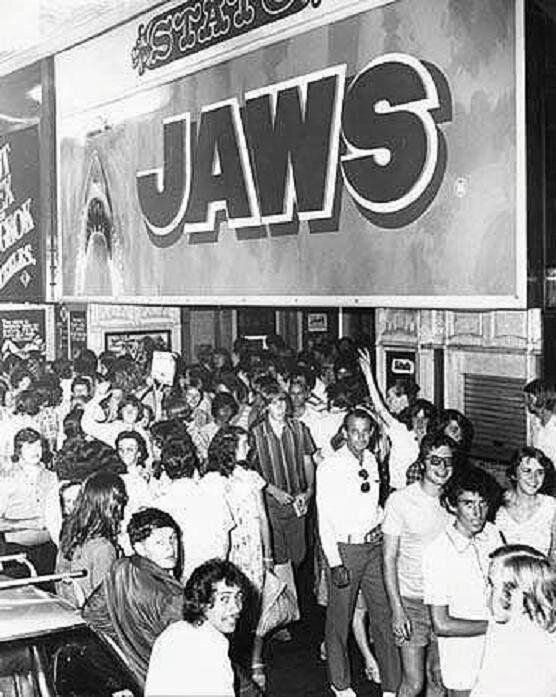

During the summer of 1975 – it opened in the States on June 20, although was originally planned to open in December 1974 – the beaches were empty but the cinema seats were full, and screams and popcorn filled the air. As was witnessed by Spielberg and Gottlieb, who would often sneak into screenings just to see the audience reaction from the back.

After only 38 days on release in the US it crossed the magic $100 million barrier and became the highest grossing film of all time, a crown it would keep until Star Wars two years later in 1977. In 1975 however, it was the summer of the shark and Jawsmania.

If we weren’t seeing sharks on our cinema screens, then they were on our walls, in our nightmares and we even thought they might be in our bathtubs. The grip of Jaws is still so powerful that most swimming pools will hear the Jaws theme be uttered and a hand fin cutting through the water.

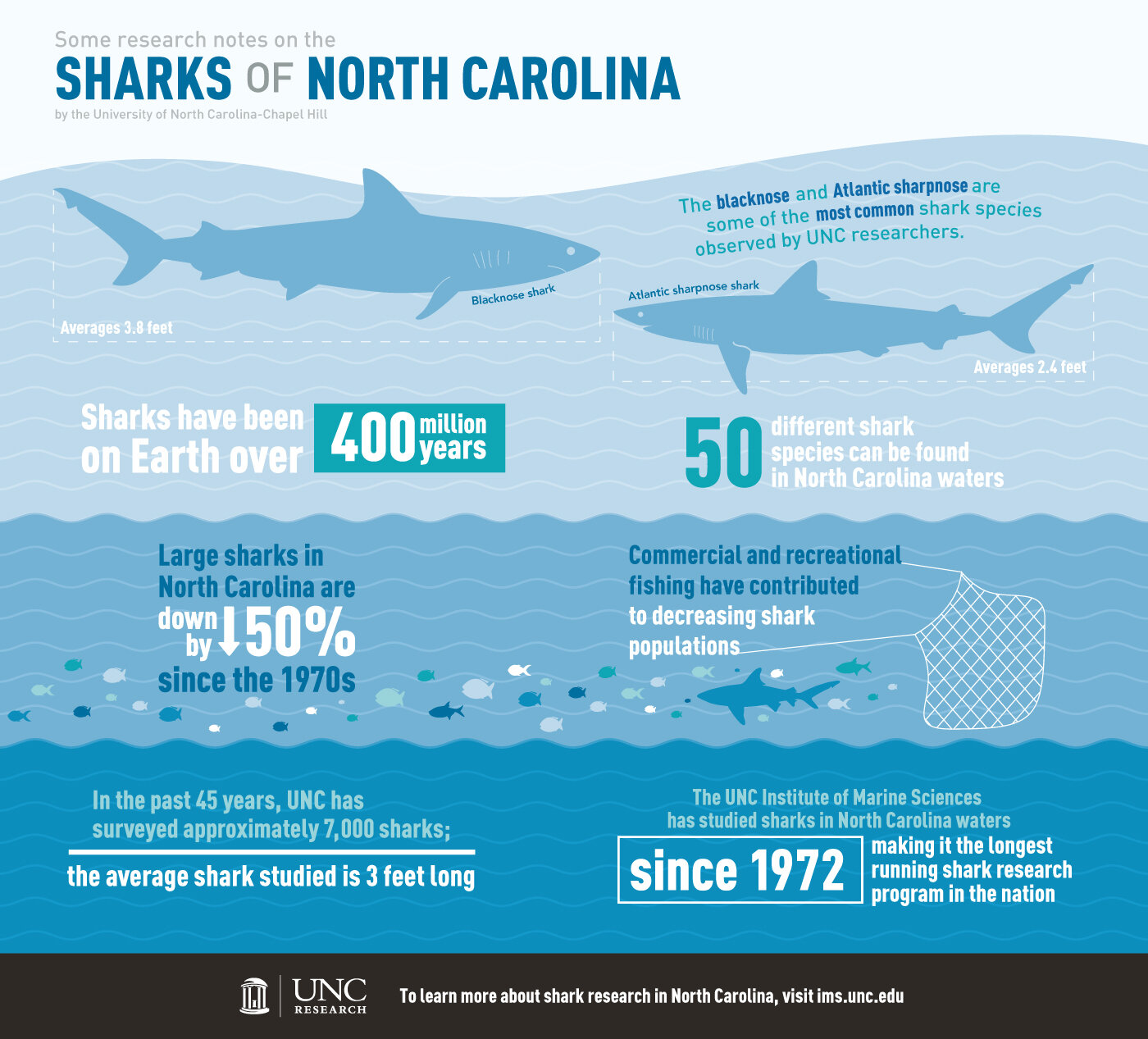

There are those that accuse Jaws of encouraging our fear of sharks and the death of sharks through hunting, but man was terrified of sharks long before Jaws – just look at the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 – and shark hunting was a thing long before Jaws.

If anything, Jaws has given us a boatload of real life-Matt Hoopers, whether that be shark scientists, people who study and photograph sharks or people who just want to discover more about these amazing creatures and help raise awareness in how we can save them.

It’s over-fishing for decades and made-made global warming that is putting the sharks at most harm, so with Jaws inspiring several generations of people to go into that field and continue to be ‘in sharks’, it will be the power and love of Jaws that will ultimately save sharks and not destroy them.

And there’s no need for us to prove that and get our name into the National Geographic, that’s hopefully a lasting legacy that Peter Benchley – who himself became a conservationist – and everyone involved in bringing Jaws to the screen will be able to be proud of.

Words by Dean Newman