The Shark Just . . . Dies: An Appreciation Of Jaws Author Peter Benchley

In Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel Jaws, why does the shark just . . . die at the end? This is more commonly expressed as: “Spielberg was a genius to change the ending of Jaws. Why the heck did Benchley choose such a lame ending?” But gather ‘round, my fellow Jaws fans. While Spielberg was 100% correct to change the ending for purposes of his film, I have recently re-discovered a small, quiet passage in Benchley’s Jaws, one which (I will now try to convince you) helps explain why the shark just . . . dies at the end of the novel. In re-discovering this passage, I have come to understand the hidden humanity and optimism in Benchley’s otherwise dark and gloomy writing. It is a passage that I can only appreciate now, as an adult, over 45 years after I first read Benchley’s work as a teenager.

First I must give credit where credit is due. If your interest extends at all to the Benchley novel, you must - absolutely must - listen to the 2009 audiobook version, with Erik Steele’s narration. Until I heard Mr. Steele’s talented voice enunciate every sentence -- from the first word of the first chapter until the last word of the last chapter -- I did not really understand what the novel was about. Jaws is not high literature, and it is true that Benchley wanted to write something his publisher could sell. (Violence? Yes! Sex? Absolutely!) But young Peter Benchley in 1973 was also a recent Harvard graduate, the son of Nathaniel Benchley and the grandson of Robert Benchley, from a family of serious writers and gifted observers of culture and wit. It is fair to assume that he chose his words with care and deliberation.

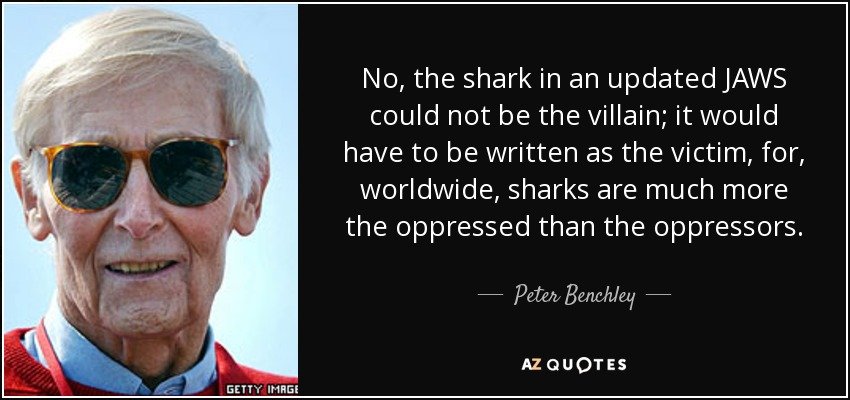

By 1973 Benchley had become fascinated by a real-life creature - the great white shark. However, in his novel, Benchley isn’t writing a heroic adventure about “finding courage” (which was the theme of the later Spielberg film). Instead, in his novel, Benchley introduces the shark as something that (in his words) “exists on instinct and impulse,” and then (I argue) writes so as to pose the question: Are we, as humans, doomed to likewise be nothing more than the sum total of our most base instincts and impulses? Benchley’s initial answer is that we humans are not as far up the evolutionary ladder as we like to think we are. The human characters are not merely “unlikable” - they are ghastly. But this is clearly deliberate on Benchley’s part.

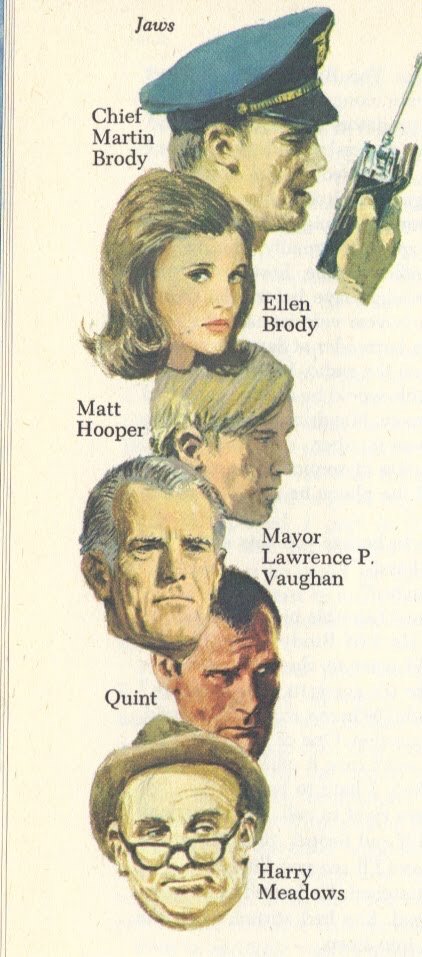

illustrations from the 1974 Readers Digest edition

The characters do despicable things to each other, driven by greed, insecurity, and fear. The mayor is a crook. Martin Brody’s wife Ellen is driven to betrayal by her toxic insecurity. Even Brody himself is no boy scout. Brody doesn’t seem to bat an eye when, in Chapter 3, the mayor cruelly observes that the first victim Chrissie Watkins “was a nobody . . . she won’t be missed.” Brody passive-aggressively sulks about his wife’s social climbing, and in Chapter 10 Benchley reveals that Brody’s motivation for joining the Orca expedition is based partly on his “obsession” with uncovering his wife’s betrayal. These. Are. Not. Nice. People.

Director Steven Spielberg with author Peter Benchley on the set of Jaws (1975)

Benchley paints the character of Matthew Hooper - introduced in Chapter 5 - as being particularly vile. As Joseph Andriano points out in his 1999 book, Immortal Monster: The Mythological Evolution of the Fantastic Beast in Modern Fiction and Film, Benchley describes Hooper’s interaction with Ellen using predatory language that almost exactly parallels that which Benchley used to describe the shark itself. Read for yourself, for example, the scene in Chapter 8 which Hooper and Ellen meet for a clandestine lunch, and Hooper first perceives Ellen’s willingness to betray her husband:

Something’s happened, Ellen thought. She wondered if he could sense -- smell? Like an animal? -- the invitation she had extended. Whatever it was, he had taken the offensive. . . . Hooper ran his tongue over his lips and leaned forward . . . .

And the following scene in which Ellen recalls Hooper in the act:

[Ellen saw] a vision of Hooper, eyes wide and staring -- but unseeing . . . . Hooper’s teeth were clenched . . . From his voice there came a gurgling whine, whose tone rose higher and higher with each frenzied thrust . . . . He was oblivious to the being beneath him . . . . Ellen had become afraid -- of what, she wasn’t sure, but the ferocity and intensity of his assault seemed to her a pursuit in which she was only a vehicle . . . .

Benchley’s point is clear: Humans prey on each other by instinct and impulse like . . . a shark. Like it or not, this Brody-Ellen-Hooper business is not just a sub-plot. It’s arguably the main plot. You may not wish to read a book about a failing marriage, in which the author uses a great white shark as a metaphorical mirror of the viciousness of the human characters. But that’s the book that Peter Benchley wrote in 1973.

But was Benchley’s view of humanity in fact so grim? Did he really believe that we are doomed to be driven only by our own most awful impulses? Having re-read the novel now as an adult, with adult eyes, I see that Benchley was, in the end, a humanist. I believe that Benchley’s point in ending the novel in the way he did was to say that we are not doomed, that there are small moments in our lives when we can decide not to act on our impulses to be cruel, selfish, and spiteful. In those small moments, we find our humanity, and a greater foe is vanquished than perhaps we realize.

There is a small passage buried at the end of Chapter 13, after Brody has stepped off the Orca, having witnessed Hooper being gruesomely devoured. Brody feels defeated, and is shaken by Hooper’s death. He knows the battle with the shark will be over soon, one way or another. Before his death, Hooper had denied having sex with Ellen, having given the transparent lie that he had spent the afternoon with Daisy Wicker. Brody walks up to a telephone. He knows Ellen has betrayed him and, at that moment, we would expect Brody to do what he and all those around him have done throughout the story: follow his impulse and - driven by jealousy, fear, and spite - call Daisy Wicker and then confront Ellen. But what does Brody do at this moment instead? As Benchley writes: “. . . But he suppressed the impulse and moved on to his car . . . .” Right there. That’s it. In that one simple sentence, Brody has done what no character in the book (including Brody himself) had done up to that point: He found his humanity. In that one crucial moment of grace and forgiveness, he broke the cycle and saved his relationship with his wife, his family, and those he loved.

When I read Jaws as a teenager, I saw this as insignificant passage. Mere filler. But now that I am older, I see that Brody’s small decision to resist his “impulse” to respond in kind to Ellen’s cruelty is in fact the final resolution of the story. Therefore, the fate of the shark - the monster that (in Benchley’s words) embodies that brutal “instinct and impulse” - has been determined. All that is left is epilogue. The next day, the shark, exhausted from the struggle, makes its final lunge at Brody. And then:

Nothing happened. [Brody] opened his eyes. The fish was nearly touching him, only a foot or two away, but it had stopped. And then, as Brody watched, the steel-gray body began to recede downward into the gloom . . .

In Spielberg’s brilliant film, a character named Martin Brody finds his courage, and so the film’s shark explodes in a perfect cinematic ending. In Benchley’s novel, a very different character named Martin Brody found something very different: His own humanity. And so that shark just . . . dies.

This essay is dedicated to Peter Bradford Benchley, 1940 - 2006

Words by Samuel Eliot Morison

If you would like to write for The Daily Jaws, please visit our ‘work with us’ page

For all the latest Jaws, shark and shark movie news, follow The Daily Jaws on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.