How The Jaws Movie Set The Bar For Creature Horror & Why It Cannot Be Replicated

Introduction

We tend to remember Jaws as the shark that wouldn’t work—and therefore the film that discovered the terror of suggestion. That legend holds water, but it ignores the deeper truth: Jaws is an editing movie first, a sound movie second, and only then a shark movie.

The creature emerges from Verna Fields’s scalpel and John Williams’s pulse as much as from any animatronic hull. Half a century on, that constraint still reads like intent; you feel it in the drift to a buoy bell and the vise‑tightening dolly zoom on Chief Brody.

This essay argues that Jaws (1975) remains the benchmark for creature horror because its terror arises not from a visible monster but from a unique confluence of oceanic production risk, editorial craft, evolutionary psychology, unannounced allegory, event‑style marketing, and sociocultural consequences. Together, these factors formed an unrepeatable ecology of fear.

The Ocean as Unruly Co‑Author

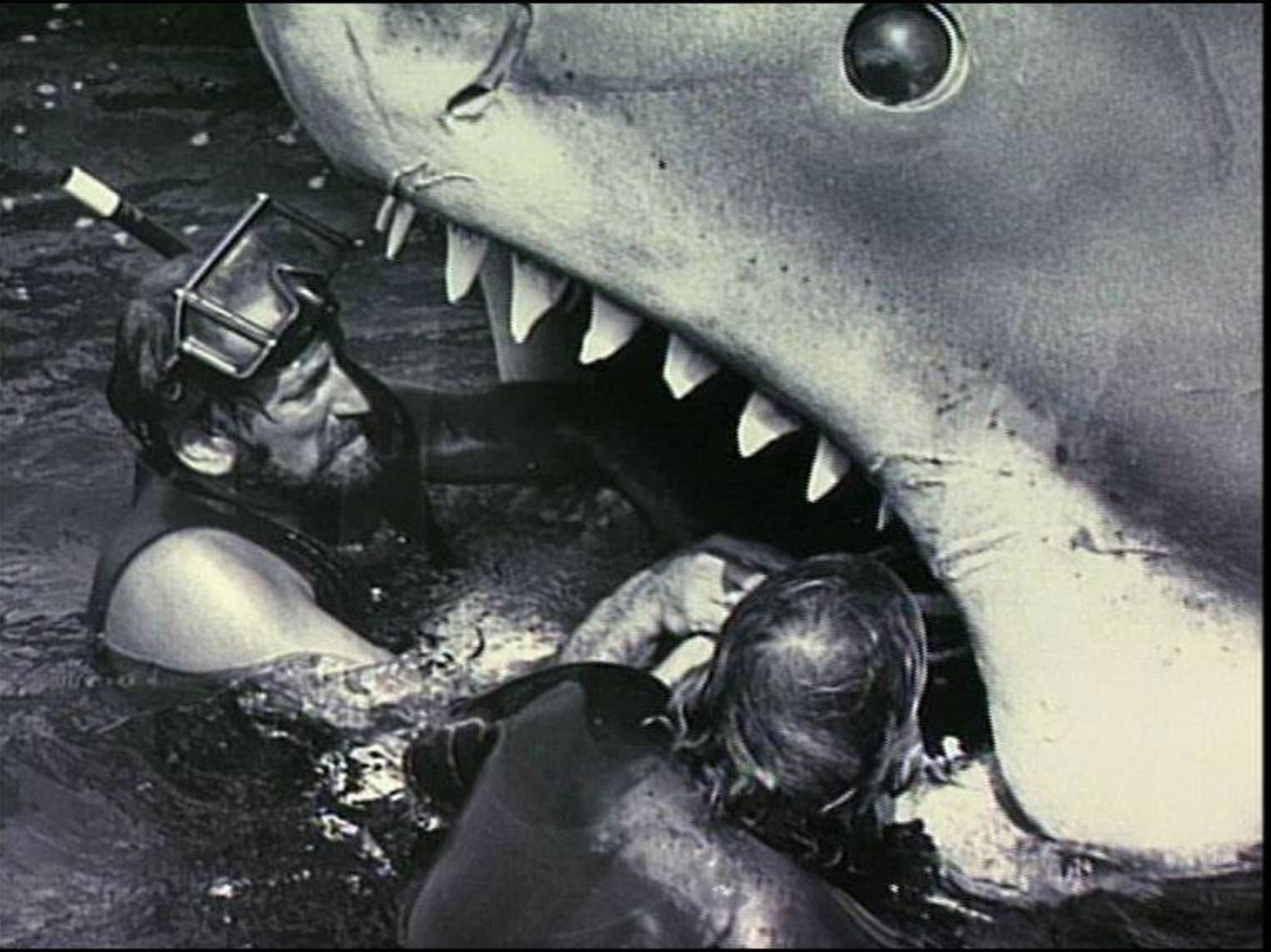

Shooting on open water gave Jaws a realism tanks couldn’t mimic, and an agony they always avoided. Boats drifted into frame; continuity dissolved in waves; seasickness and actor tensions mounted while the three mechanical great whites (nicknamed “Bruce”) repeatedly failed.

The production blew past the schedule by more than 100 days and doubled its budget, forcing Steven Spielberg to stay calm while inventing solutions on the fly. Those failures birthed the film’s grammar of implication: POV shots, empty frames, and musical cues that signal the monster's presence when it isn’t seen.

Today’s creature cinema largely removes such chaos. Digital pipelines normalize texture, stabilize continuity, and guarantee monster visibility. Ironically, that competence reduces existential dread; the ocean in Jaws was not just a setting but an antagonistic system that edited the film with the crew. Replicating that system would require embracing production risk that few blockbusters would tolerate.

Verna Fields’s Scalpel: The Edit as Creature

If the ocean authored uncertainty, Verna Fields structured it. The beach sequence stacks foreground bodies to occlude the horizon, tempts misidentification (a shriek that isn’t the shriek), then triggers the dolly‑zoom that compresses Brody’s space as fear expands.

Negative space becomes an instrument; the cut delays the bite until the imagination has already supplied it. That design makes the editor, not the shark, the primary mover of horror, a hard‑to‑copy arrangement when modern workflows assume the creature’s constant presence.

Evolutionary Psychology of the Unseen Threat

Jaws also map neatly onto evolved anti‑predator mechanisms. As Clasen argues, the scenario of predation by a malevolent agent compounds fear with uncertainty: the shark’s attacks are unpredictable.

Yet the score alerts viewers just ahead of the characters, inducing anticipatory dread. The film, therefore, meets “input specifications” of our defensive cognition, sound as signal, opacity as danger, so that a four‑minute creature can haunt every frame.

Allegory Under the Waves: Adaptation Without Announcement

Spielberg and Carl Gottlieb joked that Jaws was “Moby‑Dick meets An Enemy of the People,” a line casual retrospectives repeat but seldom unpack.

Rees and Holt’s scholarly analysis shows how Jaws operates as a “non‑announced” adaptation, a civic‑denial allegory in which political and commercial pressures (tourism dollars; summer bodies on sand) become complicity mechanisms.

That polysemic layer intensifies the horror because the monster isn’t only a fish; it’s a culture that prioritizes profit over reality.

Marketing That Behaves Like Horror

The eventization of Jaws, 409 theaters at launch, blanket national TV ads, poster art that weaponized upward‑angle menace, didn’t merely sell the movie; it extended its fear.

Audience anticipation was primed like a score: the campaign taught us to listen for danger before the first frame rolled. In this sense, distribution behaved like narrative design, wide release, and broadcast saturation functioned as off‑screen suspense.

In fact, the film's promotional aspect is still alive, in the form of Jaws-inspired games on popular sites like Quickwin Casino. Games and merchandise like this show that the movie's craze is still alive and thriving.

Cultural Consequence and Ethical Gravity

Any attempt to “do Jaws again” must confront the Jaws effect: altered public perceptions of sharks, documented shifts in beach behavior, and decades of conservation work by figures like Wendy and Peter Benchley, who sought to correct the myth the film galvanized.

Anniversary reporting and new documentaries now frame Spielberg’s remorse and the ecological stakes of monsterizing apex predators. This ethical load is part of why replication doesn’t just fail artistically; it risks harm.

Why You Cannot Replicate Jaws

The alchemy for Jaws is unique. It is something that was cooked up by restrictions. Here they are:

(a) An unruly ocean that interfered with production logic.

(b) mechanical failure that demanded invention.

(c) editorial architecture that is the creature.

(d) a score that encodes anticipatory fear.

(e) a civic‑denial allegory that broadens the threat.

(f) marketing that behaves like suspense.

(g) ethical gravity that haunts any imitation.

You can borrow restraint, and you should, but recombining all these conditions is improbable. As recent anniversary documentaries suggest, Jaws endures precisely because its terror emerged from constraints no one wants to relive.

Coda: The Practical Lesson

Modern filmmakers can still learn from Jaws: let failure force form; let absence carry threat; let editing and sound, not spectacle, do the heavy lifting.

And if you build an “event,” consider your ecosystem, what your creature myth does beyond the theater.