How Steven Spielberg Saved Jaws

John LeCarre once said that having your book made in a movie was ‘like seeing your oxen turned into bouillon cubes’.

It’s a fair point. How many times have you heard someone say (or thought it yourself), “yeah, it’s ok I suppose. But its nothing like the book”. The thing is, ‘filming a book’ is an almost impossible task - especially when you’re led to believe the book in question is about one thing (a killer shark) but it turns out to be something totally different (a slow trudge through small town politics, jealousy, the Mob, racism and a pretty clunky extra marital affair).

I was far too young when I plucked a second hand copy Jaws off a bookshop shelf - just 12 years old actually. But it was only 30p (still written inside the cover in pencil) so I was well chuffed.

I took it home and started reading that day. It wasn’t exactly like the movie, but that was ok I told myself (even if there were great chunks of it that made no sense whatsoever to my young brain) this was a book and it was the basis for my favourite film - things were bound to be a bit different.

But I soon came to realise that to make a great movie out of it, the director had to change a hell of a lot.

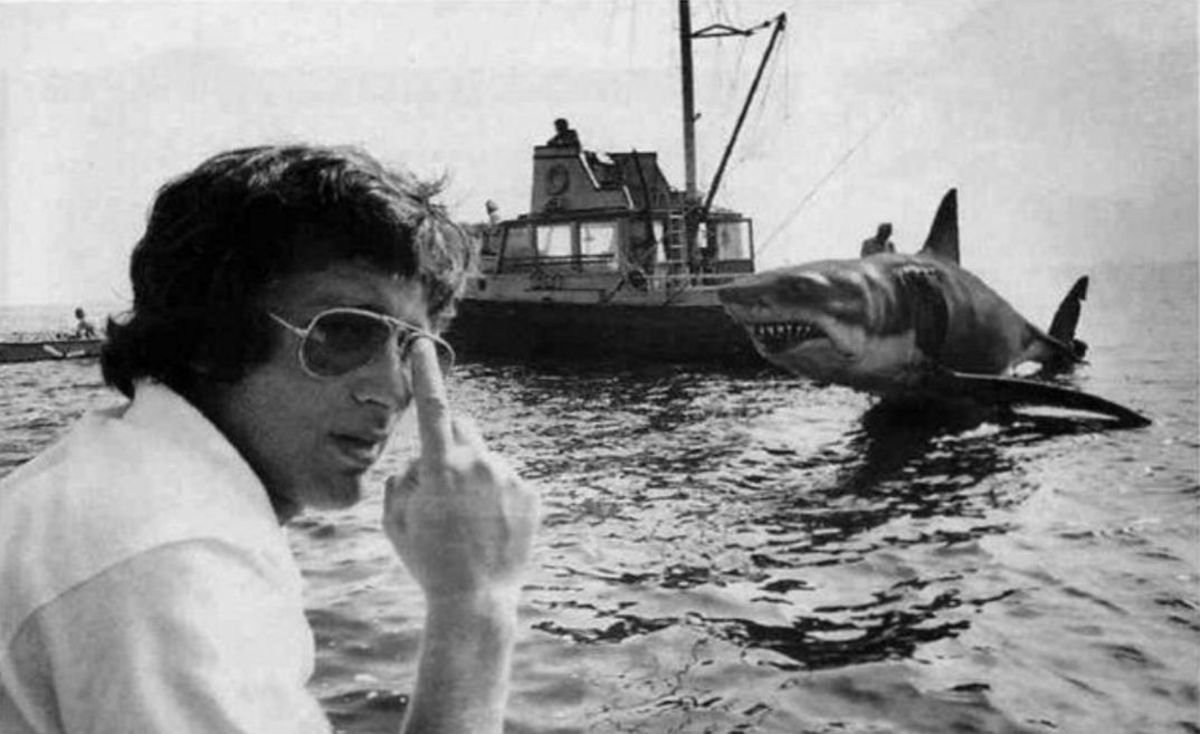

Steven Spielberg makes a call during the production of Jaws

First off, there’s no beach party. Just a big house with lots of drinking and people having fun but definitely no guy playing guitar or campfire.

The attack on Chrissie follows pretty much the same lines though. It’s lighting fast and shocking, like the shark would’ve been, and just as frightening.

You see the shark beneath the waves and there’s explanation about how it senses Chrissie’s jerky swimming pattern and how hard it hits her. She doesn’t quite understand what’s happened but knows something’s not quite right. Then she feels for her leg. It’s not there.

And the fear washes over her like a wave.

Then she’s dragged under.

And that’s about it.

It works brilliantly on the page and its terrifying.

But there’s no clanging bell, no cutting back to Tom on the beach, all drunk and useless. One minute Chrissie’s there and the next, she’s gone.

To be honest, it’s the best bit of the entire novel. After this it goes a bit off course - to say the least.

Jaws director Steven Spielberg with actress / stuntwoman Susan Backlinie (Chrissie Watkins)

Spielberg knew he’d have to change things for the movie. He wanted a straight ahead adventure story. He’d pack it with what would soon become his trademarks (the apparent safety of the family unit, small town America, Everyman characters, shooting stars…) but chuck out anything that didn’t directly serve the story he wanted to tell. Which is the basic rule of thumb of any story.

In the book, the next character we meet is Hendricks at the police station. You can see why this scene didn’t make it into the movie. All we get is the name of the girl and that Hendricks reads trashy novels and uses homophobic slurs. Oh dear…

In the movie, all this is taken care of when Brody gets a phone call. By cutting out Hendricks, Spielberg has Brody front and centre and we meet our lead character.

The movie version is already a much tighter affair.

Roy Scheider got to play Brody mostly thanks to his performance in The French Connection. An ex-boxer with a friendly face but a definite weariness to him (like he’s gone one too many rounds and just had enough of the fight).

Consequently, he looks exactly like a man who’d escaped being a cop in 1970s New York would do.

In the book, Brody is slightly less appealing.

He ogles the young girls at the beach and worries that his wife does the same to the younger men. A cynical small town cop, local to Amity and he’s sick to death of it.

This is not the pleasant Chief of Police from the movie, this was a man who resented his wife and family and had given up.

Ellen in the novel isn’t much like her movie counterpart either. We don’t get is the soft, caring mother and wife Lorraine Gary gave us. Benchley paints her as a restless woman who reckons her friends deserted her because of who she married. Like Martin, she’s bored. She still cares for her family but also worries she’s turned into her mother, a woman who hated everything once she’d had children. She wants cocktail parties and shopping trips and admits to herself she takes out her unhappiness on her husband…

Benchley created a cast of hard-nosed, cynical townsfolk, thoroughly fed up with their lives. When Spielberg read the book he saw the potential for a movie but he also found himself rooting for the shark as the characters were all so thoroughly unlikable.

In the movie, Larry Vaughn uses a single phrase to point out the precarious nature of Amity’s economics. ‘Amity is a summer town, we need summer dollars.’ It’s a perfect example of saying lots with very few words.

The book spends a good deal of time examining this idea and while it’s vital to the plot, a film about a killer shark doesn’t need lots of detailed passages on carpenters fleecing the inhabitants with shoddy work and how low rental prices of homes will derail the economy or how people had to move away to find work. It’s like when you sat down to watch The Phantom Menace for the first time expecting lots of spaceships and excitement but what you got was aliens discussing trade embargoes and people blathering on about voting in the senate!

Another big difference between page and screen is the section about the beach closures. In he movie, Brody does it because he knows its the right thing to do. In the book, its not really with an eye on public safety, its more about economics. Brody figures a two day closure should be enough for the shark to swim off and after that he can reopen them. Why bother telling anyone about the attack on Chrissie Watkins if he doesn’t have to? So in the book, Brody is of exactly the same mind as the Mayor.

We get no clash of viewpoints, just a bored police chief trying to do as little as possible.

There’s no discussion on the ferry, at this point in the book Brody hasn’t even talked to the Mayor.

And if you follow this line through, in the novel it’s 100% Brody’s fault that Alex Kintner gets killed.

This is all because Brody being a born and bred islander. He grew up with the knowing that the town will only survive if it has a great summer. It’s in his DNA to protect the livelihoods of the people above all else.

Added to this, Chrissie wasn’t a local, so there’s a real air of ‘so what’ about her death.

It seems Amity only means friendship if you’re from there.

Spielberg knew that by switching things around and making Brody an out-of-towner, they could recast him as more sympathetic. He’s a man who takes public safety seriously, not a guy who’s just rolling the dice and hoping for the best.

Steven Spielberg examines the dead Tiger shark in Jaws

Another big character change by Spielberg was the Mayor. Everyone knows Vaughn from the movie - brash, loud and wearing so much nylon and viscose, if he stood next to an open flame he’s go up like a firework.

In the book, it’s like Benchley’s writing about Roger Moore in all his 1970s 007 prime!

‘Larry Vaughn was a handsome man…a body kept trim by exercise…he had developed an air of understated chic…He dressed with elegant simplicity, in timeless British jackets, button-down shorts and Weejun loafers.’

And yes, the novel actually does say ‘button-down shorts’ which should probably read as ‘button-down SHIRTS’ but I guess it was the proof reader’s day off.

But just think how much Vaughn’s movie clothes inform his character and how it really wouldn’t have worked for Murray Hamilton to be walking around like he’s just stepped off the pages of American GQ. In both book and film he’s a slimy real-estate agent but in the novel he has an invisible business partner at his firm and it’s even implied he might’ve rigged the election.

Harry Meadows discovers the Mayor wants the beaches to stay open, despite the danger, so he can keep property prices high and his invisible partners (the Mob) can keep making money. The detail offers clarity as to exactly why he behaves as he does, but having him just another corrupt and greedy businessman is enough reason for the movie. His small-town Nixon works wonders for the movie. The Mob subplot is surplus to requirements.

Next to be axed was the affair between Hooper and Ellen. In the book this takes up quite a lot space and like the Mafia plot, it doesn’t move anything forward.

And as a 12 year old, I really didn’t want to be reading this sort of stuff!

Sharks eating people? Yes - bring it on! All that other stuff? Er… NO THANKS!

The illicit meal where they discuss fantasies, is actually quite shocking. It’s demeaning to Ellen’s character (and women in general) to have her saying the things she does and to have it in the movie - especially as written - would’ve have been a mistake.

And then we come to the final act.

Spielberg knew he needed a big exciting sea hunt but he also understood that while he’d brought in light and shade to the cast of characters, the plot needed it too.

And so we come to The USS Indianapolis Speech.

The soliloquy allows the film time to breathe. Like a lull in a storm, a stretch of flat calm ocean before the next wave rears up - but of course those still waters hold a terrible secret.

They’re filled with fear and patrolled by death.

We realise what we thought was respite is actually a ghost story of unimaginable horror.

In these few minutes below deck onboard the Orca, Jaws shows what words can really accomplish. There’s no fancy camera angles and no frantic cutting. Just a man who, when we first met him, was a crude, hate-filled thug - but reveals his entire backstory, laying bare why he is the way he is.

The script has us doing the unimaginable, we are sympathising with Quint.

In the book Hooper is swiftly devoured beneath the waves (no last minute escape for our oceanographer here) and for some inexplicable reason, Benchley brings the men back to shore on several occasions instead of keeping the Orca out at sea and maintaining the tension.

The shark dies after Quint shoots multiple harpoons into it and then, as it’s about to bite down on Brody, it suddenly stops and sinks, trailing Quint behind it.

Director Steven Spielberg with Jaws author Peter Benchley

Peter Benchley strongly disagreed with Spielberg noisy finale and ultimately had to leave the set. He later came to terms with what he called ‘the shark exploding like an oil refinery’ and agreed that it was exactly what should happen to Bruce.

Spielberg’s simple view was that if he had the audience for the preceding two hours, they would accept anything he did in the last few seconds of the film. And he was right.

In the novel, Amity’s town populated by damaged souls that needs to be purged of its sins. That’s why the shark turns up. It is essentially vengeance (no, not the same shark from Jaws: The Revenge).

The book mines a similar to the Clint Eastwood movie, ‘High Plains Drifter’. Here, a stranger arrives in a small town (next to a large body of water) and proceeds to destroy it and its inhabitants. The identity of the stranger has never been formally established but various theories have him as the devil or a ghost.

And Spielberg’s quite a fan of Clint, so you never know…

As Quint says “…when he comes at you, he doesn’t seem to be living…” and the voiceover for the original Jaws trailer, ominously intoning that ‘it is as if God created the Devil and gave him…Jaws’.

Without Peter Benchley’s fascination with the ocean and then a publisher offering him a fee to write the novel, there would’ve been no movie. But without Spielberg’s decision to do away with every part of the book that didn’t directly involve the hunt for the man-eating monster, popular cinema would’ve been radically different - and a whole lot less fun.

‘Books and movies are like apples and oranges. They both are fruit but taste completely different’. - Stephen King.

Words by Tim Armitage

If you would like to write for The Daily Jaws, please visit our ‘work with us’ page

For all the latest Jaws, shark and shark movie news, follow The Daily Jaws on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.