Charlie Does Surf! Is JAWS A Vietnam Movie?

A young idealist and a grizzled and embittered veteran, led by a bewildered, out-of-his-depth officer, must enter a hostile natural wilderness to fight a cunning, implacable and savage enemy…

This may sound like the outline to a movie set in the jungles of Vietnam but suppose the enemy was not the Men in the Black Pyjamas but the Man in the Grey Flannel Suit?

By the release date of Jaws in 1975, America’s involvement in South-East Asia had just reached its bitter and bloody conclusion. April of that year had seen the fall of Saigon and the final, brutal reunification of Vietnam, while that same month, the US had washed its hands and left Cambodia to its horrific and tragic fate at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. But more than a decade of fighting left profound scars on American society and culture at its deepest levels, not least on the moviemakers spawned during and after the violent upheavals of the 1960s and 70s.

Unsurprisingly then, Vietnam was soon to become grist to the mill amongst the new generation of directors that included Steven Spielberg and who were now beginning to make their presence felt in Hollywood. The so called ‘Movie Brats’ became part of New Hollywood, keen to add, in their inimitable style, their own voices to the terrific groundswell of popular opinion condemning the war and the American leaders who had driven them into a conflict few – even the leaders themselves – had seemed to want and who, in doing so, had brought the fighting into the very streets of the nation.

Targets, by one of this new generation of directors, Peter Bogdanovich, was released in 1968, and presaged the growing phenomenon of PTSD with its story of a Vietnam veteran whose apparently clean-cut exterior masks a tormented, compulsive gun collector who snaps and goes on a killing spree. Sixty-eight also saw the release of The Green Berets – John Wayne’s foray into Vietnam, which unsurprisingly does its best to treat the Viet Cong as the black-pyjamaed threat to Liberty and Freedom you’d expect from a Duke movie. The two films are about as diametrically opposed as is imaginable and do a good job in representing the polar-opposite views both on the War and in the styles of their filmmaking – very much New Hollywood versus the Golden Age, which by now was looking a little tarnished. It’s also perhaps worth pointing out that 1968 also saw the zenith and nadir of US involvement in Vietnam, the year opening with the Tet Offensive by communist forces that pretty much signalled to anyone with eyes to see that the War was now unwinnable for the Americans.

Two years later, 1970 saw the arrival of M*A*S*H on the big screen. Directed by one of the paragons of New Hollywood, Robert Altman, it’s set in Korea, but its black humour and grim realism exposing the insanity of life on the frontline could so easily have been set in, to quote Kenny Rogers, another ‘crazy Asian war’. (The movie is noteworthy for a minor acting turn from Carl Gottlieb, Jaws’ Harry Meadows, author of The Jaws Log, and co-writer on Jaws 2 and Jaws 3D.)

Other ‘Movie Brats’ followed Bogdanovich. In Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver, Robert De Niro’s cabbie became the poster boy for the traumatised Vietnam veteran. Hal Ashby also dealt with the damage done to those who fought in the War, in this case both mental and physical, in 1978’s Coming Home. That same year saw the arrival of what might be considered the first great Vietnam movie, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, another film that, while a true war movie, is motivated far more by the relationships between the various characters before they go off to fight, and by their subsequent fates.

Then, of course, came 1979’s Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s Homeric ode to the War and perhaps Vietnam’s answer to “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” It was also the first movie to really embrace Vietnam as a drug-fuelled rock’n’roll war although the most memorable piece of music from film is that favourite of Hitler’s, Richard Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries.’

Another Movie Brat late to Vietnam was Brian De Palma, whose Casualties of War was released in 1989, by which time Reagan was in the White House and Top Gun had seen a return to good old John Wayne-esque martial values.

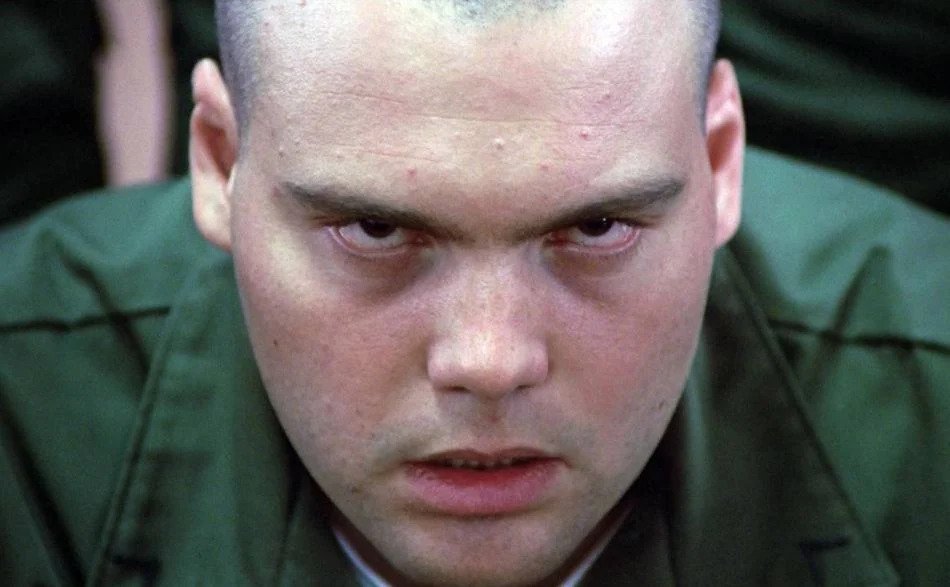

The two directors most closely associated with Steven Spielberg are Stanley Kubrick and George Lucas. Kubrick took on Vietnam in Full Metal Jacket, although the film is perhaps best remembered for its first act as the Marines are trained and prepared for the War, whilst the two most memorable characters, neither of whom make it to Vietnam, are R. Lee Emery’s Gunner Sergeant Hartman and his incredibly imaginative tirades of abuse, and Vincent D’Onofrio’s tragic Private Pyle, whose PTSD reaches its violent zenith before he even sees a battlefield.

Lucas’s Vietnam credentials are a little more complex. His most successful film prior to Star Wars: A New Hope was American Graffiti, which sees a group of young men (including a very young Richard Dreyfuss) enjoying a last night of American 60s pop culture freedom, replete with hot-rods and diners, before shipping off to the Nam. Lucas is also on record as saying that the mythos of Star Wars, at least in the context of the original trilogy, was inspired by the Vietnam War: a group of ragtag rebels, be they Alliance or Ewok, fighting – and eventually bringing to its knees – the massive firepower of a mechanised industrial superpower.

But Lucas’s involvement with Vietnam goes a little further back, to the late 60s and the early days of bringing Apocalypse Now to the screen. A protégé of Coppola, it was he and film student buddy John Milius who originally conceived the idea of Apocalypse Now, planning for Lucas to direct a cheap verité, documentary-style movie from a Milius script in black and white, using real soldier and amateur actors to emulate the nightly news reels showing on TV at the time. But the movie deal with Coppola’s company fell through and Lucas left it (and his friendship with Coppola) behind to make Star Wars and movie history, while Coppola took over the reins of Apocalypse Now.

Steven Spielberg, John Milius and George Lucas

Milius is of course well known by Jaws fans for claiming responsibility for Quint’s Indianapolis monologue. Interesting to note, then, that the speech is laced with historical inaccuracies but fair play – Quint (and Shaw) was pretty drunk when he delivered it. However, the erstwhile libertine zen-fascist director/screenplay writer took the War head on in 1978’s Big Wednesday, in which three surfing buddies reunite after one has served a tour in Vietnam (Milius’ surfing influence on Apocalypse Now is very apparent…). This was followed by 1991’s Flight of the Intruder, pretty much the only Vietnam movie to address the air war. Considering Milius’ politics, it’s unsurprising that the real enemy here isn’t the North Vietnamese per se but the ludicrous Rules of Engagement imposed on the American fliers by Washington politicians (although the president at the time the movie takes place – 1972 – was Richard M. Nixon. Not exactly your average handwringing liberal Democrat…)

Milius’ best-known movie is probably Conan the Barbarian, the script of which was written by Vietnam veteran Oliver Stone. Stone’s experiences as a grunt were transferred to the Silver Screen and turned into Oscar™ gold as Platoon. And it’s this movie that could be said to draw the most parallels with Jaws.

Consider the opening paragraph of this article. The ‘young idealists’ are exemplified by Platoon’s Chris Taylor, played by Charlie Sheen, and Jaws’ Matt Hooper. As Paul Weller wrote in The Jam’s Burning Skies, ‘ideals are fine when you are young,’ and it’s easy to suppose that both, driven by their beliefs, did not go in the direction their families expected them to. In Chris’ case, it’s made obvious that his relationship with his parents has become fractured, communicating as he does via his grandmother. The reason, it can be surmised, is the idealism that has driven him to drop out of college and volunteer to fight. In Hooper’s case, his wealthy family (“You rich?” “Me or the whole family?”) might not have expected him to go off and become a marine biologist. Having counted money all his life, he seems to be more the doctor or lawyer type. Even so, Hooper is in love with sharks as much as Chris is in love with freedom and democracy. However, those youthful ideals do not survive first contact with the enemy.

Both men soon find themselves in an existential conflict with those around them: in Chris’ case the moral and ethical battle with Sergeant Barnes (surely Tom Berenger’s finest role?), in Hooper’s case the class war with Quint. Both end up winning, Chris conclusively, executing Barnes with an AK, while Quint can’t help but admire Hooper’s scars and even ends up conceding that maybe the solution to killing the shark rests with the young marine biologist and the cage the fisherman had been so keen to mock.

Barnes and Quint are both cut from the same tough, Ahabian cloth, both left scared and cruel by their respective wars. Barnes’ nemesis, Willem Defoe’s Elias, talks of having served several tours in Vietnam and you get that feeling that Barnes is equally long serving. Perhaps with his scars he really wouldn’t be comfortable anywhere else. Quint, of course, bears his own scars.

Both men also believe they are the ones running the fight and will brook no interference. On the Orca, Quint is adamant there is only one captain. Hooper drives the boat and Brody chums. As he growls at the young man he considers ballast when Hooper has the audacity to question his methods, “Don’t you go telling me my job.”

Barnes’ treatment of the platoon’s lieutenant is just as scalding, if a little more brutal, smacking the officer over the head with a radio then berating the incompetence of the latter’s ‘fucked-up fire mission’. This perhaps smacks of Quint’s view that there are ‘too many captains on this island’, his acknowledgement of his so-called superiors barely hidden beneath thinly veiled, withering contempt. Both treat Mark Moses’ Lt. Wolfe and Chief Brody as little more than children – Quint explaining how to knot a rope with the cadence of a parent showing a child how to tie its shoelaces, while Barnes’ delivers a contemptuous ‘yes, sir’ when Wolfe stutteringly tries to chastise the sergeant for giving orders the lieutenant should be issuing to his men.

As for idealism, neither have much time for it. As Barnes puts it, “There’s the way it ought to be and there’s the way it is.”

Yet for all of Quint and Barnes’ boiled-leather toughness and experience, it’s Wolfe and Brody who are in charge, at least theoretically. It’s Wolfe’s platoon and Brody’s charter, but neither are much use. They are unprepared for the situation they find themselves in and soon, both find themselves effectively demoted, side-lined and leaving the running of the fight to those with more knowledge and experience. Of course, their respective fates are somewhat different, Brody becoming the hero, Wolfe dying in ignominy.

The ‘enemy’ in both films, the Communist guerrillas and the great white shark, would seem, at first glance, to draw few parallels, and yet… In 2001, following a series of shark attacks on the Florida coast, and with nothing better to write about that ‘silly season’, Time magazine christened that period ‘the Summer of the Shark’ in its cover story for the 28 August issue. But following 9/11, satirical media outlet The Onion took its scalpel-sharp wit to the media’s unwarranted obsession with shark attacks with an article entitled “Sharks: Terrorists of the Sea,” a sharp nod to the realisation that now more or less everything would be seen through the lens of terrorism. Bear in mind as well that there had been even more attacks the previous year.

Whether viewed as freedom fighters, guerrillas or terrorists, the Viet Cong attacks are just as sudden, unexpected, violent and terrible as a shark attack while the intelligence, the cunning, of both shark and the Viet Cong – Bruce and Charlie, if you will – are underestimated by their antagonists. And they both attack from the shadows. As the saying went, ‘the night belongs to Charlie’ so it’s hardly surprising that the late-night singsong aboard the Orca is interrupted by Bruce’ unexpected attack. In essence, they are both ambush predators, both killing machines perfectly adapted to perform their respective roles. Bruce has been fine-tuned to do nothing but “eat, swim, and make little sharks.” Compare Hooper’s awe-struck depiction of Bruce to the description of the Viet Cong’s northern allies by another Vietnam movie sergeant, Frantz, played by Dylan McDermott in the greatly underrated Hamburger Hill:

“What you encounter out there are hardcore NVA – North Vietnamese – motivated, highly trained, and well equipped.”

Vietnam movie sergeant, Frantz, played by Dylan McDermott in the greatly underrated Hamburger Hill

He goes on to add, his words mirroring the reverence in Hooper’s portrayal of Carcharodon carcharius, “If you meet Han or his cousins, you will give him respect and refer to those little bastards as Nathaniel Victor. Meet him twice and survive, you will refer to him as Mister Nathaniel Victor.”

Both the shark and the guerrillas are completely at home their environments, making them very tough opponents. The shark is a miracle of evolution honed by evolution to hunt and kill in the great blue-green expanses of the ocean while Charlie is very much at home in Vietnam’s vast rainforests – what the GIs called ‘the Green Machine.’ Their opponents come from small towns and from cities, far removed from the great natural wildernesses they have been dispatched to do battle in (or on). Both ocean and jungle can look beautiful, they can look vast and empty but their depths, their deep shadows mask a quick death to the uninitiated and ignorant. Hostile natural wilderness indeed…

You have to wonder what happened to Amity after the Orca departed. Was the attack in The Pond the equivalent of the Tet Offensive 1968 – unexpected, devastating, Larry Vaughan a pin-striped LBJ left to ponder the ruins of Summer as Johnson had looked on helplessly as his dreams of a Great Society was torn apart with civil strife? Was Amity a microcosm of the USA, never to recover from the blood spilt in its name, the land of picket fences and prom nights and July Fourth fireworks forever sullied? Was there a memorial to the dead? Were Chief Brody and Matt Hooper feted and venerated? Was there a parade? Or did they slip ashore, unnoticed and unremarked, ignored by a town trying to forget what they had endured like the grunts arriving home to a country that could hardly bear to look upon them and what they represented? Either way, I guess that’s speculation for another time.

The Orca departs Amity Island in Steven Spielberg's Jaws

Of course, once all is said and done, let’s not forget that Spielberg is not shy about dealing with war and has portrayed it at its absolute worst. But just not Vietnam. His oeuvre has centred very much on the Second World War, called by writer and historian Studs Turkel the ‘Good War’, and it is often seen in that context of absolutes: Fascism versus Democracy, Totalitarianism against Freedom. Good against Evil. It could be said to sit better with Spielberg’s perceived ‘clean-cut’, wholesome filmmaking than the moral, ethical, and social quagmire of Vietnam, the ambivalence of which seemed much more appealing to his peers. Yet the War had such a profound effect on America that it could not help but permeate Jaws, even if indirectly. Spielberg called the making of the film his own personal Vietnam (shades of Coppola’s own descent into moviemaking hell) while film analyst Dan Rubey considered the shark as an angel of retribution for America’s role in Vietnam. Taken as a whole then, it would seem Vietnam gave texture to Jaws so that Spielberg didn’t need to make an overtly ‘Vietnam’ movie, instead bringing to the screen a much subtler and clever allegorical one.

Words by Steve White

If you would like to write for The Daily Jaws, please visit our ‘work with us’ page

For all the latest Jaws, shark and shark movie news, follow The Daily Jaws on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.