STEVEN SPIELBERG AND JAWS: YOU'RE GONNA NEED A BETTER SCRIPT

How could that unimposing teenager who grew up in the suburbia of Haddon Heights and Scottsdale evolve into one of the most influential and successful directors of all time? This enigma could end up being as insurmountable to solve as the true meaning of "Rosebud" in Orson Welles' Citizen Kane....

In our (German language) book Steven Spielberg – Deep Focus Analyses, my co-author and I are trying to find an explanation by approaching his film oevre from different angles, e.g. his work for television, influences from other directors, religion, politics, cinematic style, music and many more.

This year, Steven Spielberg turns 75. What better way to celebrate than looking back at his first blockbuster hit Jaws which happened to be released in the summer of ’75… On this occasion I have – for the first time – translated a small excerpt from our book to English language (so, please excuse any linguistic awkwardness).

Only few might be aware of how often Spielberg has drawn on novels or other printed sources. Of so far 33 films under his direction more than twenty are based on such sort of material. One of the most famous is Jaws.

Spielberg turned the book into an instant movie classic and inscribed himself in film history. Quite an achievement for a 27-years-old director – considering that the book, screenplay and theatrical version are significantly different. Surprisingly, this three steps transformation process has not been sufficiently and systematically taken into account by most publications on the director's work.

The influence of the screenplay on the success or failure of a novel's cinematic adaptation is sadly underestimated. Long before the first camera shot is set up, the script has a great impact on whether the novel is retold in the manner of a journeyman director or adequately remodeled by a guy such as Spielberg who has made the story his own.

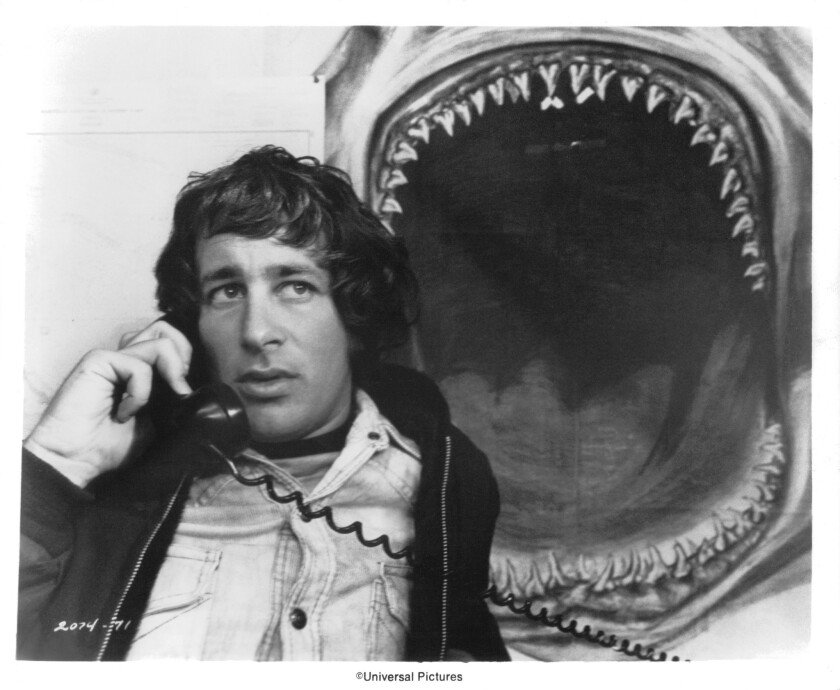

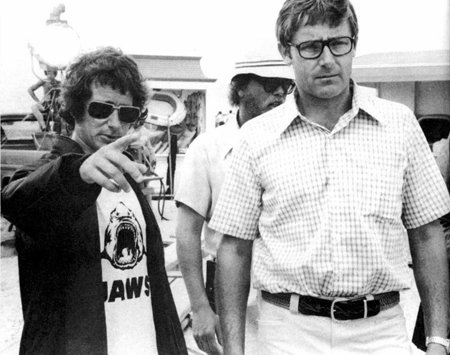

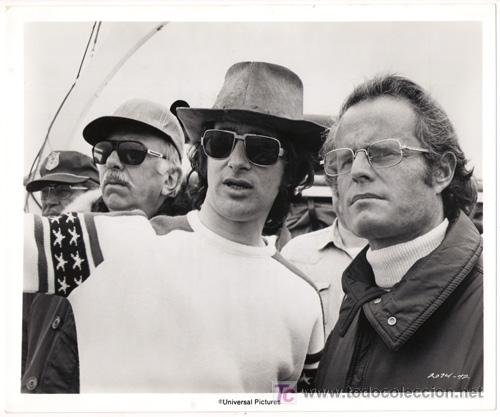

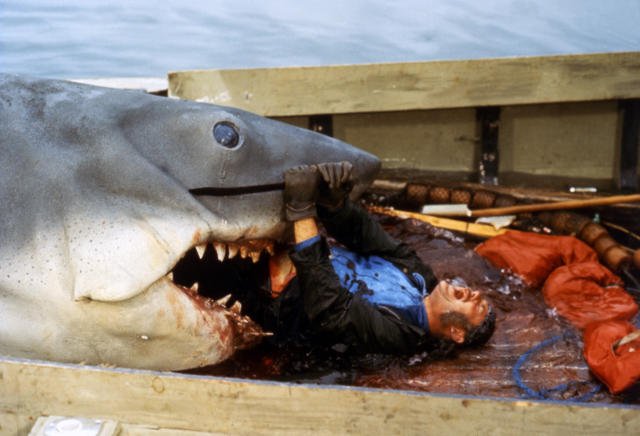

When millions stormed movie theaters to watch Jaws in 1975, it marked Steven Spielberg’ breakthrough as a smash hit director. Jaws made it to number 1 position on the list of the financially most successful films of all time. The term "summer blockbuster" was born.

No one could have predicted this when the novel’s author, Peter Benchley, submitted his 4-page treatment (titled "A Stillness in the Water") to the New York Doubleday Publishing Company and received a moderate $4,000 to complete it. When Bantam Publishing decided to shell out over half a million dollars for the hardcover version, veteran film producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown recognized the potential for a hit movie. They secured the film rights for $400,000 (an enormous amount at that time). Peter Benchley received $150,000 and another $25,000 for a first draft screenplay, which he delivered in May 1973.

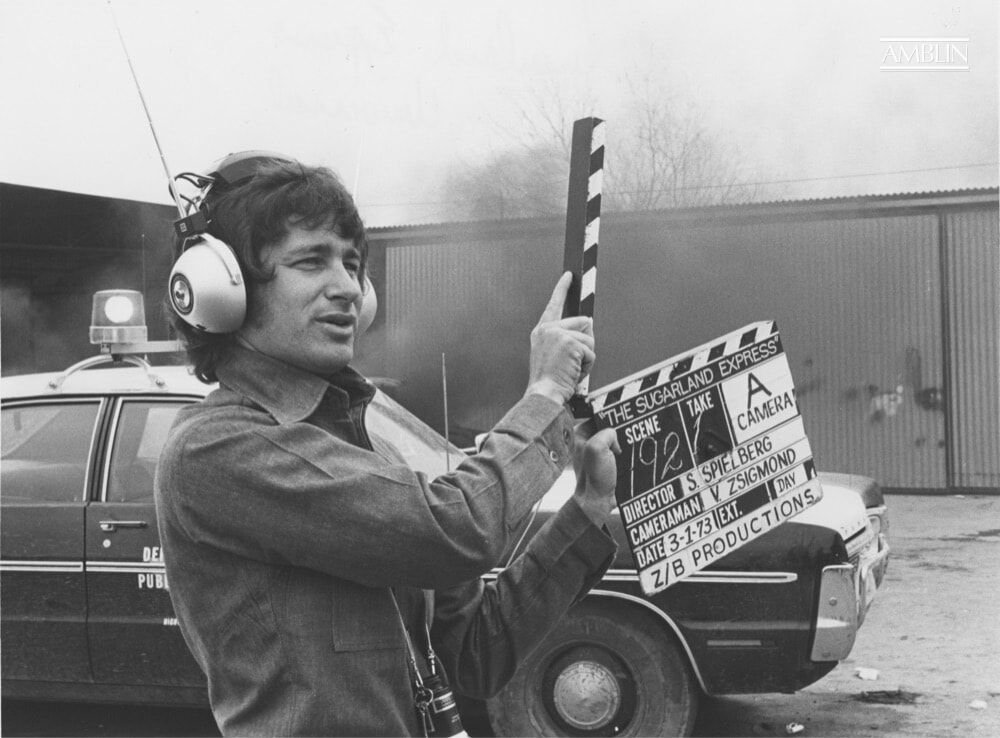

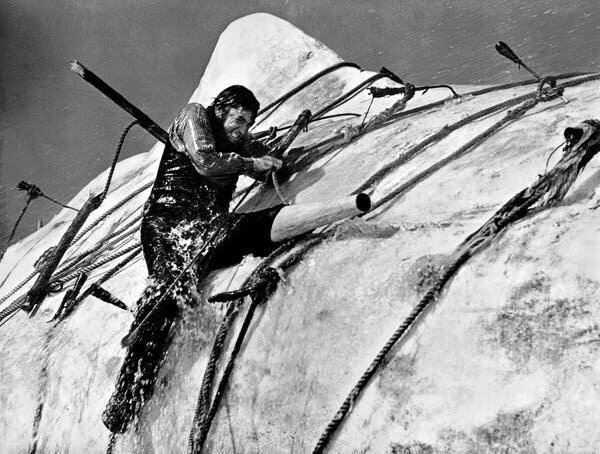

Zanuck and Brown were still busy producing Spielberg's first theatrical movie The Sugarland Express. They learned to their great dismay that Spielberg was not particularly interested when they pitched Peter Benchley's bestselling novel to their young director who replied: "Who wants to be known as a shark and truck director?". The real reason for Spielberg’s hesitance: No one had ever brought a great white shark to the screen before, and Spielberg wondered if anyone could. Back then digital animation techniques that are taken for granted today still belonged to the realm of science fiction.

Before his novel was published in early 1974, Peter Benchley made an effort to turn the 278 pages into a 120 pages first draft screenplay. When Spielberg read Benchley's first draft he did not like it at all. It was only when preparations for his film about UFOs (which, of course, would evolve into Close Encounters of the Third Kind) were plagued by delays that he accepted to take the helm of Jaws. Spielberg had Benchley write several revisions, but none of them convinced him.

In all fairness Benchley had already made significant changes compared to his novel:

Originally, marine biologist Matt Hooper seduces Chief of Police Brody’s wife. As if in punishment, Hooper ends up being killed by the shark. Benchley reduced the affair to a shy kiss on the hand and had Hooper escape alive from his underwater cage.

Brody's feeling of inferiority to his wife’s wealthy background was eliminated - as were the resulting jealousy attacks against his rival Hooper. Instead, two other strains of human weakness were applied to Brody’s character: In the screenplay version, he is afraid of the water, and acts insensitively with his son Mikey. On the other hand, some sort of friendship develops between Brody and Hooper.

In the novel, Mayor Vaughn's refusal to close the beaches is explained by his debts to Mafia gangsters who own the beach property. This side story was completely dropped, but Benchley's first draft script still addresses Vaughn's dealings in real estate.

In Benchley's screenplay, Quint‘s demise remains as unspectacular as in his novel: the shark drags him into the water and he drowns. Not a trace of the famous showdown with Brody aiming his rifle at the oxygen tank (in Benchley's version, the shark bites the tank and kills himself).

Humor and comic relief are essential elements of the film. Spielberg uses them with great effect and in contrast to the horror of the shark attacks. Some funny interludes are also contained in Benchley's script, including the following example. In this scene we get a taste of Quint's deep-seated loathing of all things academic, which is unleashed against marine biologist Hooper as the plot unfolds.

In a musical instrument store, of all places, Quint prepares for his hunt for the shark as he buys steel piano strings. A ten-year-old boy, who is about to try out a new mouthpiece on his clarinet, can no longer produce a clean sound when Quint teases him with a rhythmic roar.

In Benchley’s script, it reads like this:

32 32 INT. AMITY MUSIC STORE - DAY

Quint brushes against the counter. The shopkeeper is helping a ten year old boy fix a new teed to his clarinet. The little boy produces a mellow low tone, then wonderingly rides the scale. With little or no effort, Quint's gnarled hand floats up and drops like a sledge on the service bell. The shopkeeper's eyes pop up, the kid hits a bad note and squeaks.

QUINT

(forced politeness)

Four spools number twelve piano wire.

SHOPKEEPER

Catch any monsters lately, Mr. Quint?

Quint's eyes never leave the little boy. He is drilling him with a sidelong whammy. The boy feels Quint nailing him, and a ragged assortment of squeaks, blurps and missed notes override the sounds of the shopkeeper unspooling the piano wire.

Words by Joerg Breitenfeld

If you would like to contribute a guest blog, please visit our ‘work with us’ page