South African shark attack victim identified as woman who ran pizzeria and donated meals to homeless

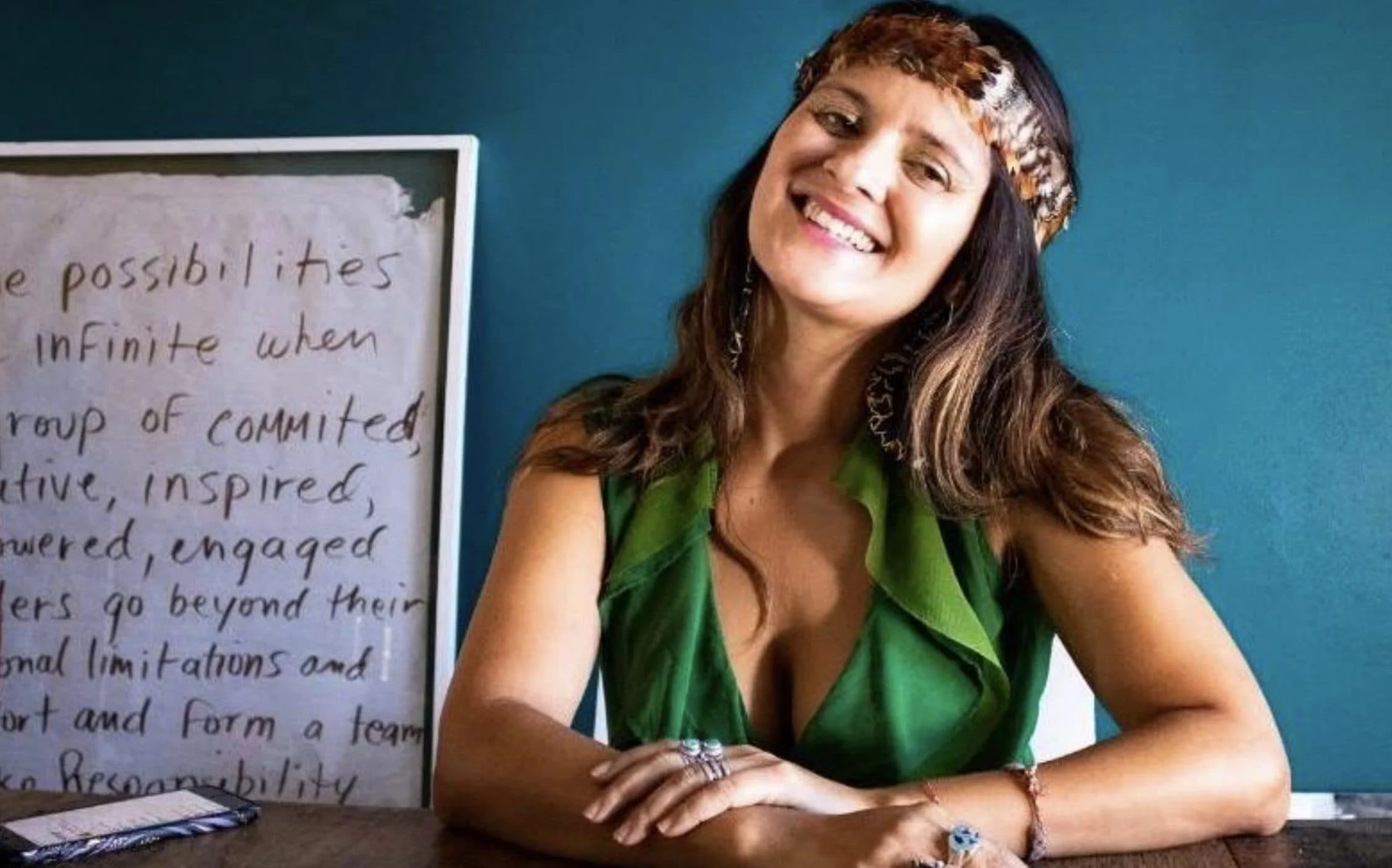

Kimon Bisogno has been named as the woman killed by a shark just 50 feet from shore in South Africa, turning a relaxing Bank Holiday into a horror day.

The 39-year-old was killed in Plettenberg Bay on South Africa's southern Cape coastline, which saw the attack take place on Sunday morning (8am, local time).

The National Sea Rescue Institute and the local authority have urged caution along the coastline, with the NSRI saying: "At this moment there seems to be more shark activities in our beaches. This is very unusual when compared with previous years."

It is thought that the shark, which reportedly plucked the mum from the edge of a group of early morning swimmers, which included her husband and daughter, was a great white. Our thoughts go out to the victim’s family, friends and loved ones.

The infrequency of shark attack deaths doesn't make it any less tragic. And that is part of the reason it is so shocking, as such horrific events are so rare.

The Daily Mail reported that an eyewitness said: 'It was a bit cloudy but there was some sun out and there were quite a few people taking an early dip as the temperature was quite warm.

"Then I just heard lots of screaming and saw people running out the water...I then heard a woman had been attacked while swimming only two or three waves out so it was quite shallow but it was said nothing could be done to help her."

Kimon Bisogno was on holiday at the seaside town of Plettenberg Bay when she was attacked by a shark

Authorities have been quick to act, with a police investigation already in full swing.

Bitou Municipality Mayor David Swart said: "We have never had a fatality at Plettenberg until 2011 and now we have had three with two in the last three months.

"We are researching into and looking at putting up a shark barrier and increased warning signage and starting our lifeguard’s season a month earlier than usual.

"There seems to be no change in the shark’s behaviour in this area so it is a bit of a mystery why we have had three fatal attacks in such a short space of time."

Some of that mystery may be explained - in part - by increased shark activity reported in the area as a result of them feeding on humpback whale carcasses that had washed ashore. Something which both the NCRI and Bitou Municipality issued a warning about just days before the attack.

All of which underlines the importance of us all remembering that the ocean is a shared environment, and many people using it know that they are taking that risk, that they could be sharing it with a shark that may, or may not, want to check them out.

Despite what you read in some media, sharks are not lying in wait for humans like some serial killer, but inevitably the paths of sharks and humans will cross and most times it will be an encounter that passes by without incident.

On the occasions that isn't the case it becomes major news, just like it does with a plane crash, precisely for the very same reason. Because such events are so very rare.

It is extremely important to reiterate that shark attacks on humans are incredibly rare, but they do happen and because of their rarity and the very nature of them they often gain widespread media and social media coverage.

The International Shark Attack File recorded that there were 73 global unprovoked shark attacks, which when you look at it globally and the increasing number of people who use the water is a low number of global incidents. But many members of the public perceive the risk of encountering a shark to be much higher than the actual statistics.

So, why to sharks attack humans?

Mistaken identity

Sharks may be popular movie villains, but they aren’t serial killers or swimming out in the sea lurking to lunge at the next human they see. And they don’t – to quote Quint – “swallow you whole”, but more take a test bite or taste test to see what they have got their teeth wrapped around.

In most instances it is a case of mistaken identity. It's long been suggested that many unprovoked attacks on humans by sharks are opportunist - after all, we are in their domain - or that the shark is mistaking swimming in the water as the thrashing of an injured creature.

Great whites are thought to be more successful in hunting prey at the water’s surface, which is where we like to play, so puts us in their path sometimes.

Research has shown that juvenile great whites are responsible for a large number of attacks on humans, and crucially their eyesight hasn't yet fully developed. Hence the mistaken identity, or should that be mistaken bitedentity?

How can you limit your risk of being attacked by a shark?

The most obvious answer is don’t go in the water (If only the Brody family had moved somewhere away from water), but those that do can take several precautions.

So, with the attack swimming high in the media, we take a look at what can you do to make sure you are as safe as you can be next time you go into the water?

How to avoid being bitten or attacked by a shark

• Don’t swim at certain times of day, sharks are nocturnal and crepuscular (dawn and dusk) predators. Swimming at these times of day, during low light and poor visibility greatly increase your risk of a shark bite, just ask Chrissie Watkins! It is also thought that more shark attacks happen during a full moon, although that doesn’t mean if it isn’t a full moon, you will be safe from a shark encounter.

• Avoid swimming near obvious signs of prey species for sharks. Large baitballs of fish, seal colonies and even washed-up whales/dolphins – as seen in The Shallows - are all signs not to enter the water.

• Avoid swimming in or near estuaries, run off from the land can attract certain shark species into these areas. Estuaries are also bodies of water where visibility is extremely low, making it harder for a shark to tell between you and a prey item.

• Avoid swimming in/around ports or harbours in areas where sharks are known to be present. Fishers often will throw discards/innards of their catch into the water in these areas, acting as a dinner bell for any nearby sharks.

• When choosing to swim in the sea, it is always best practice to swim with someone else. NEVER swim alone! In the event of a shark bite, having an additional person with you or nearby, allows them to call for help if there is an accident.

• Don’t wear jewellery, it glinting in the water could attract the unwanted attention of a curious shark.

• Don’t go swimming if you have a cut, smell is one of the strongest senses of a shark and they will smell your cut or injury. Also avoid the water if you are having your menstrual cycle.

What can you do to try and avoid being bitten or attacked by a shark if you encounter one in the water?

• Maintain eye contact with the shark, keep it within your field of vision at all times. Many bites occur when the swimmer is unaware of the presence of the shark in the near vicinity.

• Avoid erratic motions in the water. Sharks are attracted to splashes/loud noises as this mimics the motions of an injured prey species and will likely come closer to investigate. Remain calm and composed, but also don’t play dead. The shark may think you are an easy meal.

• If you have an item with you, position this between yourself and the shark. This may be a camera, gopro pole, spear gun, or even your fins. These are all items that can be used as a barrier between you and the shark if necessary.

As a last resort, what can you do if a shark does choose to be aggressive and attempts to bite or attack?

• Defend yourself by targeting the sensitive areas of the shark, this are the gills, eyes and snout. Punching hard underwater is difficult, due to water tension, as a result, a light punch on the nose is likely not going to do enough to deter the shark. Gouging in the eyes and gill area is incredibly painful for a shark, these are areas you should be targeting to defend yourself.

• Exit the water immediately!

• If you have been bitten, seek immediate medical attention, and apply a tourniquet to the affected area (as tight as possible). If a medical tourniquet is not present, a ripped-up towel, which is then rolled can act in the place of a tourniquet until adequate medical equipment arrives. Many shark attack victims don’t die from initial bites, but from the resulting blood loss.

Words by Dean Newman and Kristian Parton