How Jaws influenced American culture and changed Hollywood forever

To understand American culture in the second half of the twentieth century, we have to understand Hollywood. And to understand Hollywood in the last quarter of the century, we have to understand Steven Spielberg. And to understand Steven Spielberg, we have to understand “Jaws.”

Like Hollywood, Spielberg is most associated with spectacle and escapism. Many of the filmmaker’s most successful movies are just that. “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,” and “Jurassic Park” may not offer much in the way of introspection or social commentary but they are grand entertainment in the tradition of many of Hollywood’s greatest films. The director’s last name has been fashioned into an adjective. “Spielbergian” does not necessarily denote a particular genre but rather a kind of filmmaking built around humanistic stories characterized by wonder and sentimentality.

Richard Dreyfuss and Roy Scheider in “Jaws" (1975) directed by Steven Spielberg. Photo from the Library of Congress Collection

But Spielberg didn’t start out on that track. Previous to “Jaws,” Spielberg had helmed a handful of made-for-television features, most notably 1971’s “Duel,” a thriller about a lone driver stalked by a trucker. As Spielberg has acknowledged, “Duel” is the obvious precedent for “Jaws.” The two films have a similar appeal and employ some of the same cinematic techniques. Spielberg’s other pre-"Jaws" project was “The Sugarland Express,” a tale of a dysfunctional couple who take a police officer hostage and lead law enforcement on a long-range pursuit. Although co-written and directed by Spielberg, “The Sugarland Express” is not Spielbergian. “The Sugarland Express” is a 1970s New Hollywood movie that had more in common with 1967’s “Bonnie & Clyde” than it did with “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”

”Duel” was a success both in its domestic network broadcast and in a European theatrical release. “The Sugarland Express” got positive critical notices but the public passed on it. Spielberg’s next project would decide his future. And the film he was most interested in making was “Lucky Lady,” a dark comedy of bootlegging during Prohibition. According to the documentary “Jaws: The Inside Story,” it was Universal Studios head Sid Sheinberg who dissuaded Spielberg from “Lucky Lady” and shepherded him to “Jaws.” “Lucky Lady” may have been an interesting script but “Jaws” had much more commercial potential and after the box office failure of “The Sugarland Express” Spielberg needed a hit.

Steven Spielberg on set with actor William Atherton, shooting The Sugarland Express.

This bit of trivia reveals the way “Jaws” represents a fork in the road for Spielberg and for American cinema. The New Hollywood era was characterized by somber stories of violence, sexuality, cynicism, and moral ambiguity. Spielbergian filmmaking was its antithetical but “The Sugarland Express” and “Lucky Lady” were firmly New Hollywood movies. “Jaws” is as much a product of New Hollywood as it is a Spielbergian popcorn adventure. Consider Quint’s U.S.S. Indianapolis speech or Mrs. Kintner’s confrontation with Chief Brody or Mayor Vaughn’s crass economic calculation and his later expression of guilt. These scenes possess a moral complexity absent in many of Spielberg’s pure entertainments or "Jaws'" numerous imitators.

The production of “Jaws” has been well catalogued in various mediums, most notably Universal’s official “Jaws” documentary directed by Laurent Bouzereau and the book “The Jaws Log” authored by Carl Gottlieb. A variety of outside pressures resulted in “Jaws” being rushed into production. As actor Richard Dreyfuss recalled, "We started filming without a script, without a cast, and without a shark." The script underwent significant rewrites as “Jaws” was in production and the mechanical shark was built on the west coast while Spielberg was filming on the other side of the continent. “Jaws” lensed on the island of Martha’s Vineyard which had not hosted a major Hollywood production before and some of the locals weren’t particularly keen about its presence.Getting the last third of the movie proved to be the biggest challenge.

As often happens when Hollywood shoots on the ocean, the schedule dragged out and the budget swelled. The logistics of filming at sea were exacerbated by a mechanical shark that barely worked and frequently broke down. By the accounts of those involved, anxiety was high and tempers were short.

The stress test that was the making of “Jaws” forged Steven Spielberg.Despite the obstacles and slowdowns, Spielberg did his duty as a director: he got the performances out of his actors (including the mechanical shark) and got the shots that he needed. The faulty special effects forced Spielberg to be creative and the presence of the animal was implied through subjective camera angles, the yellow barrels, and the music. In short, the challenges made Spielberg a better filmmaker.

And despite working under considerable pressure, Spielberg exercised his artistic vision. “Jaws” is the first project in which we can observe the director’s full-throated directorial voice. Examine the attack on Alex Kintner and Chief Brody’s dinner table game with his son and the discovery of Ben Gardner’s boat and the revelation of the shark to the crew of the Orca. This is the work of an auteur and a master craftsman.

One of the key ingredients to Spielberg’s success over the years has been his collaborators. Like many successful filmmakers, Spielberg worked with many of the same people throughout his career. “Jaws” cinematographer Bill Butler shot Spielberg’s 1973 television movie “Savage.” Producers David Brown and Richard Zanuck, production designerJoe Alves, editor Verna Fields, and casting director Shari Rhodes had previously worked on “The Sugarland Express” and Alves and Rhodes would reunite with Spielberg on “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”

But the most significant collaborator of Spielberg’s career was composer John Williams.He had written a sparse but effective score for “The Sugarland Express.” Williams’ work on “Jaws” remains some of the most recognizable music in cinema history. As Spielberg has acknowledged, the music of “Jaws” is inextricable from its success. The shark theme signals the presence of the animal and the volume and tempo of the music communicate the ferocity of its appetite.

The music of “Jaws” and its partnership with the imagery is essential to Spielberg’s filmmaking style. It also prefigured the ways in which moviemaking would shift in the coming decades.

Like Alfred Hitchcock, Steven Spielberg is a master of leading the audience where he wants them to go. Spielberg’s framing of his subjects combined with Williams’ music manages our emotional reactions. Of course, Hollywood had done much of the same thing during the studio era. But following Spielberg’s lead,Hollywood’s output in the 1980s and beyond left little room for ambiguity or interpretation. That aesthetic totalitarianism accelerated at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first as Hollywood studios transformed from a movie industry to the content division of a handful of multimedia conglomerates.

And then there is “Jaws'” marketing and box office success. The movie was sold as an event and the marketing campaign was among the first to saturate television with ads. The film earned over $260 million in its initial domestic release, enough to make “Jaws” the biggest moneymaker in Hollywood history to that point.

Adjusted for inflation, “Jaws” remains among the top ten domestic grossing titles ever released. Its success began an association between Spielberg and massive box office receipts. That association would become self-perpetuating. Spielberg’s name was a marketing asset, drawing crowds to cinemas, and he continued to make films with massive appeal. The success of "Jaws" and Spielberg’s later blockbusters also created new box office expectations for Hollywood studios and their shareholders, setting the industry on a path in which spectacle films would consume virtually all of Hollywood’s financial and creative oxygen.

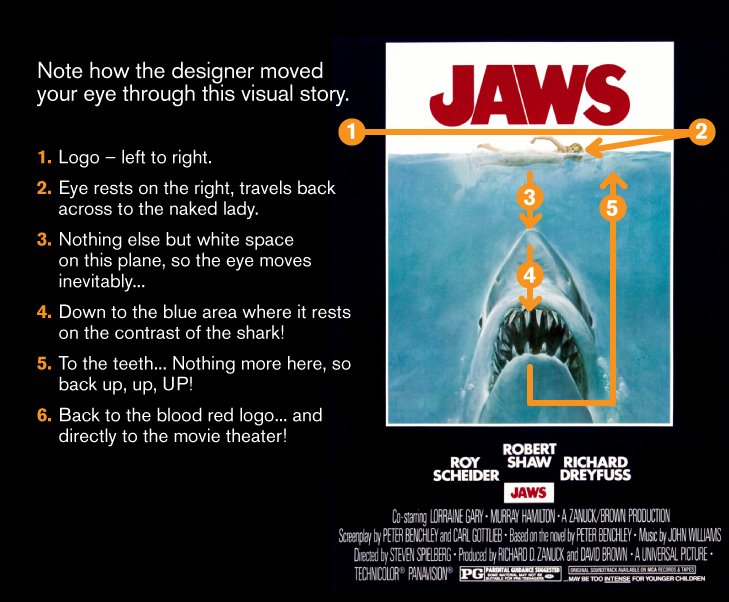

The impact of “Jaws” goes beyond Hollywood. The poster art, created by Roger Kastel for the paperback edition of Peter Benchley’s novel, is one of the most recognizable paintings of the twentieth century and Kastel’s work has been imitated and parodied in political cartoons and magazine covers.

“Jaws” birthed a cottage industry of shark documentaries and the Discovery Channel’s annual Shark Week programming, which has become its own cultural institution, owes its existence to the 1975 movie.

The U.S.S. Indianapolis speech led to a resurgence of interest in the fate of the naval battleship which resulted in the exoneration of Captain Charles B. McVay III’s court marshal and the discovery of the ship’s wreckage.

And on its forty-fifth anniversary, “Jaws” became a frequent cultural reference point during the coronavirus pandemic with numerous commentators comparing Amity Island’s reaction to the man-eating shark with American society’s response to the COVID-19 virus.

No one film or filmmaker changes Hollywood but certain movies do nudge the industry. “Jaws” is the bridge between the cynicism and moral complexity of New Hollywood and the populist and escapist thrills that defined the industry in the following decades. This is the prototypical summer blockbuster and the film’s revenues reconfigured the norms of Hollywood success.

But while “Jaws” may have arrived with a significant marketing push, it has stuck around on its own merits. “Jaws'” craftsmanship has been a source of inspiration and obsession by later filmmakers and cinematic devotees. The triangular conflict between nature, community, and individuals taps into primal and sociological truths that keep engaging viewers one generation after another but the film’s resolution of that conflict offers the Spielbergian solace that made the director so successful.

This is one of the great pieces of cinema and “Jaws” is an essential title in the filmography of Steven Spielberg, in the history of Hollywood, and in American culture.

"Jaws" was inducted into the National Film Registry in 2001.

Essay posted in January 2022 and is reproduced here with permission of the author. The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Library of Congress

Nathan Wardinski is the host of Sounds of Cinema, a public radio program broadcast by the Association of Minnesota Public Educational Radio Stations. You can find out more about his work at www.soundsofcinema.com.

If you would like to write for The Daily Jaws, please visit our ‘work with us’ page

For all the latest Jaws, shark and shark movie news, follow The Daily Jaws on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Essay posted in January 2022 and is reproduced here with permission of the author. The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Library of Congress